“This is an outline of the history of the settlement at the head of Shuswap Lake, first known as Seymour City and later as Seymour Arm.” Bill Allison, 1979.

The first settlement there in 1865, was a supply and outfitting point of men going to the gold rush strike in the Big Bend of the Columbia River and it was also the end of navigation for the steamboats. There were two trails to the Big Bend; one went up Ratchford Creek to the Columbia River, and one went over the Cotton Belt plateau.

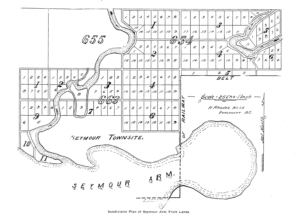

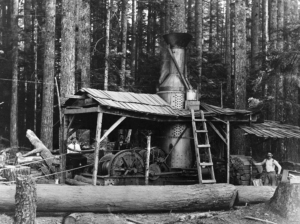

In the early 1900’s, a land development company called the Seymour Arm Estates acquired a large tract of land on the Arm which they divided into five, ten, and fifteen acre orchard sites, then advertised the land for sale all over Canada, the United States and Britain. They encouraged people to buy land and get rich growing fruit. Of course, they led people to believe all you had to do was plant the trees and sit around in the shade and watch the fruit grow ripe and profitable. However, this was far from the truth as the land at Seymour Arm was covered with debris and large tree stumps which had to be removed. This land clearing was a slow and costly business. The company brought in large steam donkey engines to pull the stumps and pile them in large piles to be burned.

The Seymour Arm Estates had borrowed money to develop their land from the Dominion Trust Company and all went well until the President shot himself and it was found that the Trust Co. was bankrupt. This ended the Seymour Arm Estates’ plans and they were placed in receivership. The settlers found that there was a large mortgage on all the property which they could not pay nor did they have the money to hire lawyers to try to get the title to their land. There were a few who managed and lived there for many years, but most of them left as there was no work except temporary work in the logging camps.

When I was a boy my father sometimes took me to watch the powerful logging machines at work. It really was an exciting experience to watch these steam engines pull these tree-length logs three to four feet in diameter through the woods. The men who operated these steam donkeys were masters of their art and as a boy, it was exciting to watch the men unloading these machines from the barges they brought them in on. They would move these big machines ahead on the barge until they were ready to tip over, then yank the throttle wide open and they would leap onto the beach. They would have a team of horses roll the cable from the first donkey out to its length and anchor to a tree. The others would attach their cable to the one ahead so when the first donkey pulled itself ahead, it would pull the cable of the second donkey out and then it would pull itself up to the first donkey and so on until they reached their work point. I think my greatest ambition as a boy was to be a donkey puncher, as the men who operated them were called. In the winter they used a lot of horses when logs could be hauled on the snow on large, two-runner sleighs, called sloops. The roads were watered to create ice roads so two horses could move large loads. They used another team called a snatch team to start the load moving

When I was a boy my father sometimes took me to watch the powerful logging machines at work. It really was an exciting experience to watch these steam engines pull these tree-length logs three to four feet in diameter through the woods. The men who operated these steam donkeys were masters of their art and as a boy, it was exciting to watch the men unloading these machines from the barges they brought them in on. They would move these big machines ahead on the barge until they were ready to tip over, then yank the throttle wide open and they would leap onto the beach. They would have a team of horses roll the cable from the first donkey out to its length and anchor to a tree. The others would attach their cable to the one ahead so when the first donkey pulled itself ahead, it would pull the cable of the second donkey out and then it would pull itself up to the first donkey and so on until they reached their work point. I think my greatest ambition as a boy was to be a donkey puncher, as the men who operated them were called. In the winter they used a lot of horses when logs could be hauled on the snow on large, two-runner sleighs, called sloops. The roads were watered to create ice roads so two horses could move large loads. They used another team called a snatch team to start the load moving

Al Bass was the first permanent settler at Seymour Arm and lived in a log cabin on the east side of the lake which still bears his name as “Bass Point”. The settlement four miles down from the head of the lake was named Albas after him. He was well past middle age when I first remember him, but was a very interesting man to know. He started life out as a trapper and hunter in the Mississippi River Valley in the days when your life was always in danger and several times he was robbed of everything but the clothes he had on, and in one occasion, nearly starved to death before reaching the nearest settlement. He followed the advance of the white man across the United States to California, taking in all the gold rushes, travelling either on horseback or with the wagon trains used before the railroads were built. His main interest in his life had been prospecting for gold, but he had apparently never been lucky enough to make any great deal of money from it. The Klondike was the only gold rush he missed and I have often wondered why. Bass knew Buffalo Bill and a lot of notable men of those days, including some notorious outlaws. I often wondered if Sam Bass, the outlaw killed by a Texas Ranger, was his brother. He was one of the most interesting men I knew to talk to.

My father, George Allison, first lived up on the bench from the lake and planted an orchard there but a few years later he built a summer home down near the lake but when winter came my mother did not want to move back to the original home, so the summer home was enlarged and we lived there for quite a few years. Then we moved onto the Gillis property and as the original Gillis house had burned down, my father built a large house there which also caught fire and burned down. Then he built a smaller log house and a few years later he moved on to a homestead on the south side of Daniels’ Bay. Then my mother became very ill and needed to be near a doctor so they moved to Kamloops where they have both passed away.

When I left public school at Seymour Arm I went to Calgary to live with my uncle and aunt and took a two-year course in steam engineering. But when I had finished that, the law would not allow anyone under twenty-one to be in charge of a steam plant of any kind except on the railroad. I worked at several other jobs and in 1928 went to work for the C.P.R. as an engine watchman, but when the depression began in late 1929 I was out of a job. So I went back to Seymour Arm until 1940 when the war began. Then I went back to work on the railroad as a fireman and later as an engineer and retired off the Canadian in 1973.

The hotel at Seymour Arm was being built by Forest Daniels when my father arrived and he worked on it until it was finished. The hotel was operated by Bert Freeman and his wife Laura for some time, including my mother when the Granby Mining Co. was doing exploration work at the Cottonbelt mine. It was deserted for many years and was about ready to collapse when new people decided to restore it and operate it in the 1960’s and now looks as good as when I first remember it.

But the most outstanding bit of history, is the Collins Mansion. The 13-room home was built by Charles John Collings, who came to Canada from England in 1910. The Collings were English people: father, mother, and two sons, Carl and Guy.

people: father, mother, and two sons, Carl and Guy.

I believe that Mr. Collings, a very famous watercolour painter whose works are in tions at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Banff’s Whyte Gallery and other private collections, was looking for a remote property where he could paint and where his sons could farm.

It is said that the Collings lived in a tent for a year while a big house was being built.

All of the materials were brought in by boat, and then transported by horse and wagon, and everything was built by hand.

As an artist he had earned enough so the sons never had to go out to work, though they did so for short periods, but most of their lives were spent continuing to build an old style English home under their father’s supervision, complete with beautiful landscaping and lots of flowers. It still is a beautiful place and so it should be having been almost a lifetime’s work for the two men.  The original house was small and built from cedar logs stood on end on a wooden foundation. Some years later they built a two-storey addition more than twice the size of the original house and it was built on a cement foundation. In Guy’s last years he built another addition to the back of the newer part of the house. It was a beautiful billiard room. The family also had a large grand piano in the living room as both Mr. and Mrs. Collings were pianists. This large piano was built into the house so the only way it could be taken out would be to take it to pieces or take the end wall out of the living room. The living room also had a large home-made stone fireplace and a lot of ornaments that Mr. Collings had brought from various parts of the world. One of those was a music box that was gifted to the Collings from former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt. This amazing music box played the big huge steel discs, so when I would go over there the one song that the boys just loved to play was “Listen to a Mockingbird”. The huge steel things would play that in a trill that this music box made it sound so incredible it almost brought tears to your eyes.

The original house was small and built from cedar logs stood on end on a wooden foundation. Some years later they built a two-storey addition more than twice the size of the original house and it was built on a cement foundation. In Guy’s last years he built another addition to the back of the newer part of the house. It was a beautiful billiard room. The family also had a large grand piano in the living room as both Mr. and Mrs. Collings were pianists. This large piano was built into the house so the only way it could be taken out would be to take it to pieces or take the end wall out of the living room. The living room also had a large home-made stone fireplace and a lot of ornaments that Mr. Collings had brought from various parts of the world. One of those was a music box that was gifted to the Collings from former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt. This amazing music box played the big huge steel discs, so when I would go over there the one song that the boys just loved to play was “Listen to a Mockingbird”. The huge steel things would play that in a trill that this music box made it sound so incredible it almost brought tears to your eyes.

Charles Collings’ son Guy lived in the house the longest, and when he passed away the house was passed down to his good friend John Rivette.

The last time I visited Guy, the old part of the house was in very bad shape as the wooden foundation had rotted away and as it was built right on the ground, there was no way to repair it but to tunnel under it and remove enough earth to make a working space under it. Guy was in his seventies by that time and said that he did not feel he could do anything with it.