An essay by Brian Wilson ©2013

An essay by Brian Wilson ©2013

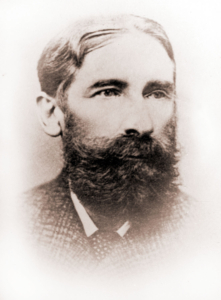

John Carmichael Haynes left Ireland in 1858, hoping to join the police force which Chartres Brew, a friend of his uncle and chief inspector of police, expected to establish in the new colony of British Columbia. They arrived in Victoria on Christmas Day 1858, and early in January 1859 Governor James Douglas appointed Haynes and Thomas Elwyn special constables to accompany Brew on an expedition to quell disturbances among the gold-miners at Hills Bar (site of McGowen’s war against the Spuzzum Natives). Haynes then served at Yale as a constable under Magistrate Edward Howard Sanders, and in November 1859 was promoted to acting chief constable.

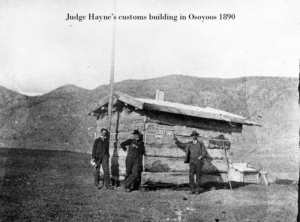

The next year Governor Douglas chose Haynes to assist William Cox, the notorious justice of the peace, assistant gold commissioner, and deputy collector of customs for the gold camp of Rock Creek. In this open range country around the Kettle River, it was easy for American traders, cattlemen, and mule-drivers to ignore the border and freight south. Douglas, to divert commerce to British hands, ordered the Hope-Princeton Trail built and stationed Cox and Haynes at Rock Creek to collect the taxes. Haynes arrived there on Oct. 15, 1860. Six weeks later Cox sent him to Similkameen, the scene of another gold flurry, where he opened a customs house in December. In 1861 the Cariboo gold rush drew miners north and by November the last miner had left Rock Creek. Inland traffic into British Columbia from Washington territory now passed through the Okanagan valley and Haynes was moved to Osoyoos Lake where he assumed responsibility for the whole area of Rock Creek, Okanagan, and Similkameen. He became deputy collector of customs in March 1862, a year in which 800 men and over 9,000 cattle, horses, and mules passed through his station, and he collected more than £2,200 in revenue by charging $6 a head for stock.

Cox remained as magistrate of Rock Creek, and later in 1861 he and Haynes had to deal with an uprising of miners and Indians. It seems a miner named Cherbart had been murdered by a young native of the Colville band. Although Cox had no jurisdiction on the US side of the border, the young man was retrieved and subsequently hanged without trial. The Okanagans, led by Chief Silhitza protested the lynching by the American miners and the fact that Cox refused to charge the whites with any crime. Silhitza travelled to the Oblate Mission on Mission Creek and had the Priest write a letter to Governor Douglas outlining the out-of-control violence against Natives in the Okanagan. He writes “that is what rouses the anger of all the Okanagan tribe which has already taken up arms. I tried to quiet the insurrection by assuring them that I have recourse to your kindness, persuaded as I am that you will give Mr. Cox instructions on the subject.” When questioned by Douglas, Cox just shrugged it off, reporting that everything was “satisfactory”. Judge Haynes had the power to stop the shooting and lynching but did nothing and native life was now changed forever.

Cox and Haynes were not finished with the Okanagans having to report many more violent problems over two years. In every case the final outcome was frontier justice. Cox failed to have any effect on relations with natives and whites. Douglas finally took him away from the magistrate job and made him Assistant Commissioner of Lands and Works, answering to Colonel Moody. Moody charged him with marking out a “reserve” as defined by the Indians themselves. Cox had a lengthy interview with Silhitza which ended in a satisfactory agreement for a reserve encompassing most of the head of the lake from Swan Lake to the Kamloops trail. Cox was sent off to do the same for the other Tribes of the Okanagan Nation. Cox despised this job almost as much as he despised the Natives.

The Okanagan Nation had been taught the value of agricultural land and many were experienced stock raisers long before the mining invasion. It made sense then, when marking out a reserve, that the Bands would chose good grazing land and winter range. They valued the land for the same reasons as the newly arrived competitors, and that was to support a quality of life. And so the land they chose was the best agricultural lands at the head and foot of the lake, well suited to subsistence farming and ranching. It would have supported them well had they been allowed to retain it.

Silhitza drew up a reserve for himself in N’kwala (Nicola Valley) and moved off hoping all was well. But then disaster struck. The Okanagans were decimated by a small pox outbreak in 1862/63. The many deaths seriously affected the population and their ability to govern themselves. Haynes showed complete indifference to the devastation of the Native population and it wasn’t long before white settlers barred their teeth and began gnawing away at the reserves.

John Carmichael Haynes replaced W. G. Cox as the Queen’s representative in the Okanagan Valley in 1862. Haynes was appointed to the Legislative Council in 1864 by Governor Fredrick Seymour and commissioned as a Justice of the Peace as well as collector of Customs. From his office in New Westminster he dealt with numerous complaints from good British immigrants. They complained that the Natives of the Okanagan had garnered all the best agricultural land and weren’t using it for anything but grazing. Haynes agreed that the reserves were far too large for the diminished population and he would authorize disposal of lands with compensation. Colonial Secretary Birch stepped into the fray and ordered Haynes to dispossess the Indians without compensation as the reserves were “out of proportion”.

Haynes was given an awesome level of power to deal with all issues of government in the south interior, near lordly, somewhat medieval. Judge Haynes returned to Osoyoos via the newly completed Dewdney Trail in 1865 to meet with surveyor J. Turnbull. They met with Chief Tonasket and travelled to Penticton to see Tom Ellis a local rancher. Turnbull did his best to map out the new boundaries as instructed by Haynes and to the disgust of Chief Tonasket. Tonasket can be credited for the retention of the best bottom lands for the Bands but the reserves on the lake were reduced to a shadow of the former acreage and common grazing lands were removed completely.

Judge Haynes was not a friend to the Okanagan Nation but he did surround himself with the elite of British Colonialists. If you arrived from the British Isles and wanted a particular piece of land, or a water license or you wanted someone to go away, Judge Haynes was there to help. Haynes surrounded himself with an Irish posse that struck fear into the hearts of all they encountered.

Attendance at the 1865 and 1866 sessions of the Legislative council strengthened Haynes’s ties with government officials. These associations proved helpful: in 1865 he obtained the power to reduce the size of the two large Indian reserves at the head and foot of Okanagan Lake, thus making meadow and range lands available for white settlement. That year Haynes also supervised the construction of a new customs house at “the narrows” of Osoyoos Lake. In August 1866 during the brief gold rush at Big Bend he was appointed district court judge at French Creek, but soon returned to Osoyoos as collector of customs. In November, when the colonies of British Columbia and Vancouver Island were united, Haynes remained on the civil list as deputy collector of customs for the southern boundary.

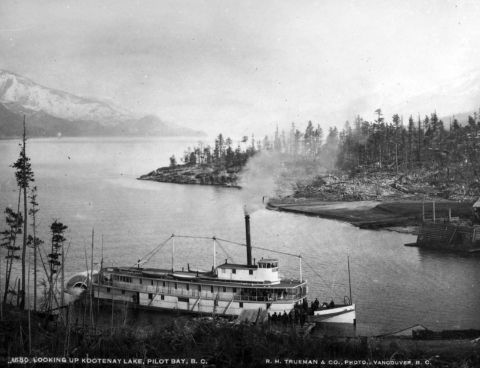

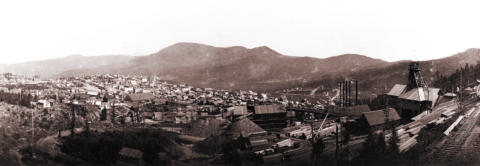

Haynes rapidly expanded his land holdings after 1872. In August 1869, with his gunman and fellow Irishman, Constable William Lowe, he acquired 160 acres of land at the head of Osoyoos Lake, to which he added an adjoining 480-acre tract the following year. In 1872, Lowe suffered a severe accident when hit by a train in Ontario. He returned to BC, but completed his duties in New Westminster until his death in 1882. At this time, Haynes had to deal with Mrs. Lowe and she demanded a considerable sum of money for her interest in the Haynes ranch. It was decided to place a mortgage on the property through the British Land and Investment Company in New Westminster. Further acquisitions between 1874 and 1888 increased his holdings to 20,756 acres. He established a horse ranch but could not find a market, and turned to cattle ranching, eventually increasing his herd to 4,000 head and acquiring the title of “The Cattle-King of the South Okanagan.” With his long-time friend and fellow Irishman, Tom Ellis, he made cattle drives over the Hope Trail to New Westminster and over the Dewdney Trail to Kootenay and Calgary. With his fine house on the shores of Osoyoos Lake, it was rumoured that his properties had a value of $200,000. Doubtless all would have been well if the Judge had lived to manage his affairs.

to which he added an adjoining 480-acre tract the following year. In 1872, Lowe suffered a severe accident when hit by a train in Ontario. He returned to BC, but completed his duties in New Westminster until his death in 1882. At this time, Haynes had to deal with Mrs. Lowe and she demanded a considerable sum of money for her interest in the Haynes ranch. It was decided to place a mortgage on the property through the British Land and Investment Company in New Westminster. Further acquisitions between 1874 and 1888 increased his holdings to 20,756 acres. He established a horse ranch but could not find a market, and turned to cattle ranching, eventually increasing his herd to 4,000 head and acquiring the title of “The Cattle-King of the South Okanagan.” With his long-time friend and fellow Irishman, Tom Ellis, he made cattle drives over the Hope Trail to New Westminster and over the Dewdney Trail to Kootenay and Calgary. With his fine house on the shores of Osoyoos Lake, it was rumoured that his properties had a value of $200,000. Doubtless all would have been well if the Judge had lived to manage his affairs.

In 1888, while returning over the Hope Trail with his two sons who had been at school in Victoria, Haynes was taken ill. He died on July 6 at the home of John Fall Allison at Princeton and was buried at Osoyoos. Judge Haynes had carried out his duties in Osoyoos and the Kootenay using a firm hand in collection of BC’s first taxes. With other Irish landed immigrants he later shared a comfortable life as a country squire in a pastoral setting, and with them established cattle ranching as the first industry of the Okanagan.

After Haynes death, Mrs. Haynes and her children attempted to continue operations but failed and the mortgage was foreclosed in 1895.

Tom Ellis, with his connections in high places was able to purchase the $65,000 mortgage for the 20,000 plus acres. Within three weeks of the foreclosure, Ellis was able to secure a judgement against the estate and forced a sale of all stock, chattels and equipment.

Mrs. Haynes was devastated to say the least. She had always considered Ellis a family friend and confidant. Here he was taking her family to the cleaners. She hurried to the coast to take court action to stop the sale. She was successful in securing a stay of proceedings. As chance or circumstance will have it, the courier carrying the documents to stop the sale failed to arrive in Osoyoos on time and the sale proceeded. Ellis was successful in keeping the pending public sale from being advertised so attendance was very small. The few who attended lacked the resources to compete with Ellis. Ellis purchased the entire estate paying $17,000 for the 400 head and the horses, $2 per ton for the hay etc. etc.

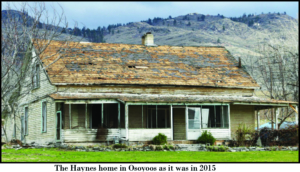

Emily Haynes was able to maintain the Osoyoos home on the west side of the lake that the Judge had built in 1882. It was an impressive two story, 10 room structure of hewn logs. She remained in it until her death.

The 50 acre property was sold to D.P. Fraser in 1917, and the Fraser family lived in the structure for three generations.

When you consider that the home is nearly the same age as the Grist Mill in Keremeos, it must have tremendous heritage value, but heritage is chronically low priority in small communities. When the Fraser family sold the property in 1990, George failed to succeed in his attempt to have it set aside as the Osoyoos Museum. They opted for the curling rink that now must be vacated.

The new owners, Harbens and Harkesh Dhaliwal, have begun to dismantle the home in preparation for a winery on the property.

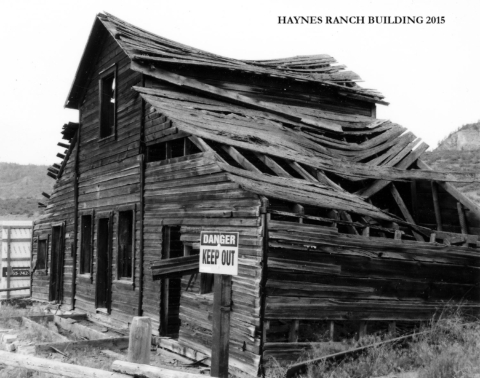

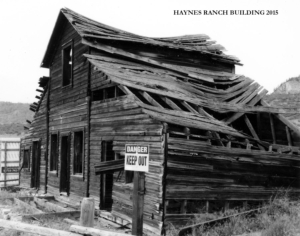

The ranch is still evident today in the skeletal remains of the buildings perched on a sandy dune on Road 22 in the regional district. Are any or all of the structures worth saving? Can they even be saved, and if so, for what? In 2015, Dave Mattes of the Haynes Ranch Preservation Committee stated they have efforts underway to try and save the mortise and tendon barn, possibly for wildlife habitat.

Editor’s note: Maybe the Haynes name should fade away. I know he was the originator of Osoyoos and Oliver, and the foremost European settler. But we need to put in perspective his position as a notorious colonialist and imperialist. His relationship with local Indigenous peoples needs to live in infamy.