THE LEGEND OF THE MASSACRE OF THE LOST CONQUISTADORS

There is evidence that a Spanish expedition from a Pacific coast port in Mexico reached the mouth of the Columbia River in 1775. Bruno Heceta and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra sailed their ships, Santiago and Sonora, close to the Columbia delta to take on supplies, as the crews were suffering from scurvy and needed a change in diet. They were set upon by the Chinookan people of the Columbia Basin and losses were considerable. A few escaped into the thick forest. This is the probable origin of the lost patrol.

Thinking that  the Columbia River was actually a bay, the conquistadors traveled upstream hoping to find a crossing away from the marauding Chinookans. But the river was very wide and went on forever. These men were seasoned soldiers with amazing survival skills who carried their faith in God as an additional sword. Without horses they would have made no more that 10 or 15 miles a day along the banks of the Columbia. Coming through the deep gorge of the Cascade Mountains, it would have taken months to just make it as far as The Dalles. From there the river got calm and the small tributaries were easy to cross. The land stretched out and became desert like. The local natives were friendlier but cautious of these dark, hairy travellers with metal weapons. The soldiers would have traded for pack dogs with the Chelan people as the Spanish had skills with pack animals of all kinds. Horses would not be seen in this northland for another 50 years.

the Columbia River was actually a bay, the conquistadors traveled upstream hoping to find a crossing away from the marauding Chinookans. But the river was very wide and went on forever. These men were seasoned soldiers with amazing survival skills who carried their faith in God as an additional sword. Without horses they would have made no more that 10 or 15 miles a day along the banks of the Columbia. Coming through the deep gorge of the Cascade Mountains, it would have taken months to just make it as far as The Dalles. From there the river got calm and the small tributaries were easy to cross. The land stretched out and became desert like. The local natives were friendlier but cautious of these dark, hairy travellers with metal weapons. The soldiers would have traded for pack dogs with the Chelan people as the Spanish had skills with pack animals of all kinds. Horses would not be seen in this northland for another 50 years.

Then they reached the mouth of the Okanogan River and were told to turn north. Looking at the sands of the Okanogan River they may have seen gold flakes, sparking some excitement of the rumour of a golden city. They turned north.

The Similkameen legend states that sometime near the start of the 1800s, a band of men with white faces and mu ch hair and wearing “metal” clothes, marched into the valley from the south and camped near the Keremeos Indian village at Cawston Creek. They remained there until an altercatio

ch hair and wearing “metal” clothes, marched into the valley from the south and camped near the Keremeos Indian village at Cawston Creek. They remained there until an altercatio

n erupted between a Similkameen man and a soldier over trading for women. The quarrel quickly escalated into a bloody battle. The heavily armed Spanish professional soldiers; inflicted heavy losses on the natives. In a barrage of stones and spears, the Conquistadors, along with several captives, retreated up the valley of Keremeos Creek.

Continuing up that stream, the legend states, the Spaniards crossed over the divide and marched down the Shingle Creek draw. At the foot of Okanagan Lake they crossed through the wetland near Snpintktn (Penticton) to the eastern side and followed the old eastside Indian trail to Nxokostan and established a camp close to a little creek a few miles north of the present day site of Kelowna. There it is speculated, they threw up a large log building to winter with their captives.

The following spring, with their numbers dwindling from either disease or hostility, they left their outpost and retraced their steps southward. The column with numbers considerably reduced, made their appearance once again near the upper reaches of Keremeos Creek.

Several days later, so the story goes, they marched out of the hills and camped on a small flat overlooking Keremeos Creek; evidently close to the area where the stream enters the valley (where the cemetery is today). Forewarned, the Similkameens kept close watch on the column

and when the Spaniards struck camp and moved off down the valley; they were ambushed and overwhelmed by a large number of Similkameens. A vicious battle took place in which the outnumbered Spaniards were annihilated.

According to the legend, the Similkameens then buried the despised white strangers with all their armor and weapons in a low, grassy mound somewhere between the last Spanish camping place and the Indian village called Keremye’us, and there, so the band Elders swear, they remain to this day.

There is some evidence that tends to corroborate the story:

Bits of old steel weapons have been recovered in various parts of the valley and especially in the area close to Keremeos. They may have been trade items from later expeditions into the Similkameen area but why were they concentrated almost exclusively around Keremeos? One such metal artefact is on display in the Penticton Museum today.

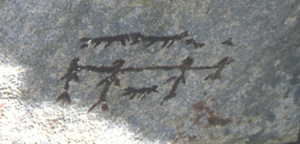

The pictographs in the valley also provide other clues, especially the “Prisoner Painting” which seems to depict four Indian warriors roped or chained together and surrounded by dogs. Isn’t it a common Spanish custom to chain their captives together and guard them with dogs? It’s an interesting theory.

The discovery of a rare native breastplate; hammered from copper, in an old burial site near Keremeos, also lends credence to the Spanish story. The piece is heavily perforated to look like chain mail. Where did the Similkameen Band get the idea of armor plate? It was singular to the Keremeos region and some historians contend that the Indians simply copied the Spanish mail they had seen or been told of, which had proven nearly impenetrable to arrows during the battles.

The discovery of a rare native breastplate; hammered from copper, in an old burial site near Keremeos, also lends credence to the Spanish story. The piece is heavily perforated to look like chain mail. Where did the Similkameen Band get the idea of armor plate? It was singular to the Keremeos region and some historians contend that the Indians simply copied the Spanish mail they had seen or been told of, which had proven nearly impenetrable to arrows during the battles.

Finally, in 1863, the ruins of a large building were discovered in the Kelowna area. The size of this massive structure, estimated at around 35’ by 75’ indicated that it had once been a winter quarters and even in 1863 was very old. Was this a building used by local peoples for ceremonial purposes or was it the place the legend says was used by the Spanish when they purportedly wintered near Kelowna?

Finally, in 1863, the ruins of a large building were discovered in the Kelowna area. The size of this massive structure, estimated at around 35’ by 75’ indicated that it had once been a winter quarters and even in 1863 was very old. Was this a building used by local peoples for ceremonial purposes or was it the place the legend says was used by the Spanish when they purportedly wintered near Kelowna?

The clues are fascinating but by no means conclusive and the mystery of the “Spanish Mound” remains in legend.

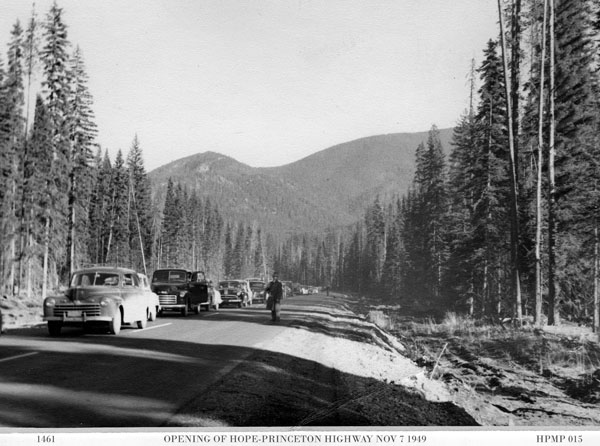

At the height of the depression, the Federal Government provided funds for construction of the road and the Province put into effect a work relief program. 40 relief camps were set along the route and workers came from all over Canada. These men worked year round in camp shacks where snow drifted in and hygiene was rare. But they did get fed regularly and could send money home to their families. Some never

At the height of the depression, the Federal Government provided funds for construction of the road and the Province put into effect a work relief program. 40 relief camps were set along the route and workers came from all over Canada. These men worked year round in camp shacks where snow drifted in and hygiene was rare. But they did get fed regularly and could send money home to their families. Some never

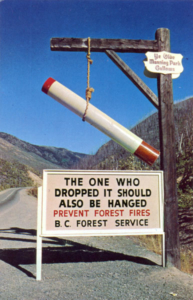

There is confusion about the history of this sign. Here’s the true story.

There is confusion about the history of this sign. Here’s the true story.