Joe Weeks was only 15 when he arrived in Priest Valley from Shewsbury, England. He spent the hot summer of 1894 helping his father build a log home on their 14 acre farm near where downtown Vernon is today.

Joe Weeks was only 15 when he arrived in Priest Valley from Shewsbury, England. He spent the hot summer of 1894 helping his father build a log home on their 14 acre farm near where downtown Vernon is today.

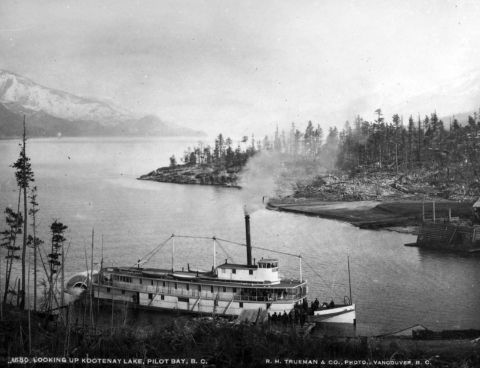

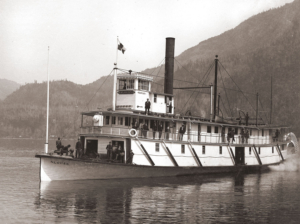

He and a couple of friends heard of the gold strike at Camp Hewitt (where Peachland is today) and decided to try to get rich quick. They took passage on the little wood-burning sternwheeler “Fairview” to Lambly’s Landing, the stopping off place for the gold field. As they travelled, they were overtaken by the sternwheeler S.S. Aberdeen, glistening white flags waving, whistle signaling mournfully. At that moment, Joe Weeks made up his mind to be on board.

Joseph Weeks walked up the gangplank as a fresh new deckhand on October 7, 1897. He learned the trade quickly. As a hardworking hand, he caught the eye of his captain, George Estabrooks, who encouraged Joe to take up studies in his off time.

He was given time off to travel to Victoria to write exams, and in 1899, he was granted a Mate’s Certificate to operate on lakes and rivers in Canada.

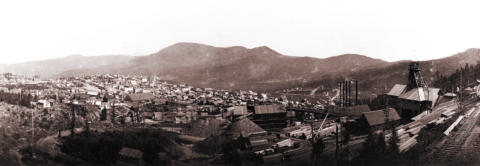

His first assignment was Mate on the S.S. Slocan that serviced the silver mines on Slocan Lake. She hauled silver concentrate to the smelters in Trail and Nelson. Joe spent 3 years on the Slocan until he was transferred to the S.S. Moyie on Kootenay Lake. This mate’s job only lasted until Joe was accepted as mate on his beloved S.S. Aberdeen on Okanagan Lake.

Trail and Nelson. Joe spent 3 years on the Slocan until he was transferred to the S.S. Moyie on Kootenay Lake. This mate’s job only lasted until Joe was accepted as mate on his beloved S.S. Aberdeen on Okanagan Lake.

In 1904, Joe Weeks was given an opportunity to take his Master’s Certificate. He rushed to Arrowhead on upper Arrow Lake to take the exam. He sailed through it with honours. CPR posted him to the S.S. York, Okanagan Lake’s reliable freight boat. He worked the York for several years and his jovial personality delighted all who sailed with him.

In 1907, Joe once more walked up the gangplank of the S.S. Aberdeen; this time as her captain. He took his place at the wheel and steamed down the lake. He took her from wharf to wharf for 6 years. In 1913, the Aberdeen, was retired, and Joe Weeks took his place on the tugs moving barges from railheads north and south. He worked the York and tugs Castlegar, Kelowna and Naramata. As he sailed the lake pushing freight barges, he watched longingly at the new luxury ship, S.S. Sicamous, that has been launched in 1914. She was one nice ship.

In 1913, the Aberdeen, was retired, and Joe Weeks took his place on the tugs moving barges from railheads north and south. He worked the York and tugs Castlegar, Kelowna and Naramata. As he sailed the lake pushing freight barges, he watched longingly at the new luxury ship, S.S. Sicamous, that has been launched in 1914. She was one nice ship.

His chance came in 1922 when he took the helm of the Sicamous. He was made for this ship and she for him. They became part of each other. He could pull her onto a beach without the slightest jar. He left rickety wharves without so much as a wake and always got the mail delivered on time. His skills are legendary to this day.

CPR decided the Sicamous was no longer economical, and she was pulled from service in 1935. Captain Weeks went back to the tugs, captaining the tug Naramata.

Captain Joseph B. Weeks retired from lake service in 1942 after 45 years on lake boats. He spent the rest of his life talking about and

collecting Okanagan history. He was a long term member of the Okanagan Historical Society.

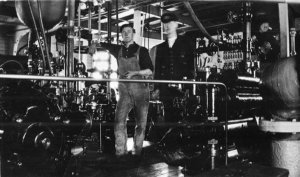

The last portrait of Joe Weeks in 1963.

With Captain Walter Spiller, left and

Otto Estabrooks, right, at the Tug Okanagan

When the Gyro Club of Penticton purchased the Sicamous from postwar CPR for a club house, Joe Weeks salvaged wood being removed from the dining deck to increase the size of a dance floor. From this wood he manufactured knick-knacks, mantle clocks and the like, which he gave for Christmas gifts for years.

Captain Weeks had married Mary Moore as soon as he received his Master’s license. They had two sons, Ludlow and Frank. Captain Joe Weeks lived to be 91. His ashes were spread in the clear waters off Squally Point.

WHO’S DRIVING THE BOAT?

While researching the former article on Captain Troup, I was puzzled with the lack of information on the training of steam boat pilots at the turn of the century. With the proliferation of sternwheeler construction, there would have been a logical need for trained, highly skilled crew members.

While researching the former article on Captain Troup, I was puzzled with the lack of information on the training of steam boat pilots at the turn of the century. With the proliferation of sternwheeler construction, there would have been a logical need for trained, highly skilled crew members.

Now I did find reference to the hiring of pilots from far afield, bringing some from lake and river systems in the U.S. Our own George Ludlow Estabrooks was practically shanghaied from the CPR station in Revelstoke when it was discovered he was a St. John riverboat captain. The labour-hungry executive from the Columbia Kootenay Steam Navigation Company put him to work on the WM Hunter on Slocan Lake in 1892. He spent the rest of his working life on Arrow and Okanagan Lake steamers.

Digging a little deeper, I did find that the federal government was very involved in the inspection and certification of boats and crews in eastern Canada.

In 1859, the navigation laws of the Provinces of Canada were consolidated in a comprehensive work of legislation which set a pattern for the regulation of steam vessels in Canada.

The greatest advance of the 1859 Act lay in the regulations for safety and inspection of steamboats. For the first time, the steamboat inspectors were required to form a regulatory body called the Board of Steamboat Inspection, with a chairman appointed by the Governor in Council. The Board, to this day the administrative authority for the safety of Canadian shipping was required to meet at least once a year as directed by the chairman. Its principal duty was to frame regulations for the safety of vessels and to examine and certify the engineers of steamboats. Certificates, awarded after examination into the “Character, habits of life, knowledge and experience in the duties of an engineer…” were valid for one year and were then subject to renewal, “provided always that the licence of any such Engineer may be revoked by the said Board upon proof of negligence, unskillfulness or drunkenness, or upon the findings of a Coroner’s jury.”

The fee for a first examination as engineer of a steamboat was five dollars, and for renewal one dollar. Collectors of Customs were authorized to collect those fees.

This research has me assuming that inspectors never came west prior to 1900 and the companies had to just pay the fees and carry on. Even a drunken pilot was better than none when competing for freight fees on the lakes and rivers.

It wasn’t until 1886 that these rules changed. Amendments to the Act made it mandatory for all pilots and rail engineers to be certified by inspectors each year. Master’s Certificate holders became an exclusive group.

The Certifications were awarded once a year after a stringent examination.

Most biographies that I have viewed, show clearly that the crews worked their way through the ranks with on-the-job training. Many of our own Okanagan Lake life-long professionals started by shoveling coal or stacking wood.

My favourite is Captain Joe Weeks.