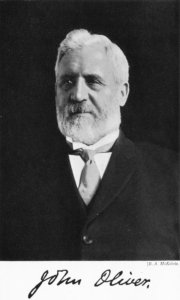

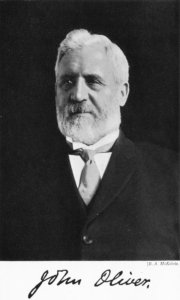

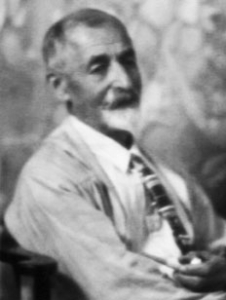

In 2015, the town of Oliver erected a memorial to Premier John Oliver. Any middle school student can tell you that he was a leader of our province in the 1920’s, but few of you readers could answer any questions as to accomplishments during his tenure. Who was he really, and why is Oliver named for him?

He was born July 31, 1856, in Hartington, England, the eldest of Robert and Emma Oliver’s eight children. John Oliver grew up in an English farming community, where his family eked out a modest living. The Oliver family immigrated to Canada, settling on a farm in 1870, in Maryborough Township, Ontario. He decided, at age 20, to travel west. On May 5, 1877, he arrived in Victoria, looking for work. He found it on the mainland of British Columbia with a survey crew of the Canadian Pacific Railway. After a summer of hard labour, he had saved enough money to start a farm, so he pre-empted land in Surrey.

While building a cabin and clearing land, Oliver was drawn to community affairs. He helped to establish a rural school and he petitioned the provincial government for assistance with roads in the recently settled district. At age 26, he was appointed clerk of the municipality; he also served as tax collector. In the fall of 1882, he resigned his positions, sold his land, and purchased a farm in Delta. Four years later he married Elizabeth Woodward, a daughter of the local postmaster. They would raise five sons and three daughters, while developing one of the most prosperous farms in the region. Oliver also earnestly applied himself to municipal affairs in Delta. He became a school trustee and a few years later he was elected to the municipal council where he served two terms as reeve.

Although Oliver loved rural life, he had set his sights on higher public office. At age 43, he took a long-contemplated step into provincial politics by running in the election of June, 1900. At the time, politics in British Columbia were characterized by intense factionalism and the absence of formal parties.

In February, Joseph Martin had assumed the premiership. Surprisingly, Oliver threw his lot in with Martin’s forces and campaigned aggressively in Westminster-Delta. On June 9th, Martin’s group went down to a crushing defeat, electing only 6 members to a house of 38. Oliver experienced his first important political triumph, however, winning his seat.

By aligning himself with Martin, Oliver had identified himself as a Liberal, in opposition to the government of millionaire coal miner, James Dunsmuir. Certainly, Oliver’s own brand of liberalism was shaped by his rural conservative roots. He earned the nickname “Honest John” for his principled pursuit of a legislative inquiry in 1902-3 into railway land grants that helped to bring down the government of Dunsmuir’s successor, Edward Gawler Prior, in June 1903. This scandal pointed the accusatory finger directly at CPR governor, Lord Shaughnessy, who attempted to dispose of undesirable granted lands for blocks that looked promising for oil deposits.

With Prior forced to resign, Richard McBride formed the next government. He immediately called an election and announced that it would be the first in British Columbia to be fought along party lines. Even though Oliver had had a falling-out with Martin, there was little doubt that he would campaign as a Liberal. On Oct. 3rd, 1903, he was returned in Delta with an increased majority.

In the fall of 1909, Macdonald was appointed to the bench, creating a vacancy in the position of provincial Liberal leader. Oliver had emerged as his chief lieutenant and was the obvious choice for the post. He became leader with insufficient time to prepare for the general election, called for Nov. 25th, 1909. A vociferous critic of the government’s railway policy, he decided to make it the centerpiece of his campaign. He disapproved of the recently negotiated contract with the Canadian Northern Railway for a line from the Alberta border to Vancouver, arguing that the province was not obliged to assist a private railway and that the details of the contract should have been made public before the election.

For the first time in almost a decade, Oliver would not sit in the legislature; he lost in the two ridings he had contested, Delta and Victoria. There were reports that $60,000 had been spent to defeat him.

Early in 1912, McBride called a provincial election. With increased public revenues and little opposition, the Conservatives were poised for another easy victory.

On March 28th, 1912, Oliver suffered another political setback and the Liberal party was completely shut out of the legislature. It was difficult to believe that there was a future for the Liberal party in the province. Oliver’s political career and dreams of higher public office were were seemingly finished.

The provincial economy was unable to sustain rapid levels of growth and headed into a recession as World War I broke out. On Dec. 15th, 1915, McBride surprised many by resigning the premiership. In the spring of 1916, two Liberals, including Brewster, the new party leader, won by-elections. When Bowser took his Tories to the polls late in the summer, he faced a more organized Liberal party with some new, reformist ideas. In 1916, Oliver was successful in Dewdney as part of an impressive electoral victory; 36 Liberals, 9 Conservatives, and 2 independents were chosen. The Liberals began a quarter century in which they would be the dominant force in British Columbia’s politics.

Oliver was appointed by Brewster, the new premier, to two cabinet positions, agriculture and railways. In both portfolios he applied himself keenly, inspired by the Liberal victory. Agriculture was a natural choice for him. He took great pride in his understanding of the challenges faced by farmers and he believed that a strong agricultural sector was vital to the province’s future. He also concerned himself with the soldiers who would return from the war and wanted to ensure that they would have the opportunity to own and develop farms in rural areas of the province. “Thinking over these problems in the night,” wrote his biographer, “an idea occurred to him. He got out of bed, and sitting in his nightshirt . . . he drew up the Land Settlement (and Development) Act.” This landmark legislation, passed in 1917, would be dubbed the “nightshirt” act. John Oliver successfully urged the federal government to establish a national policy for the settlement of returning soldiers.

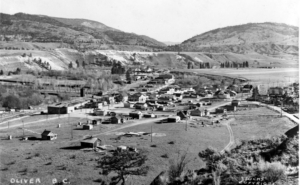

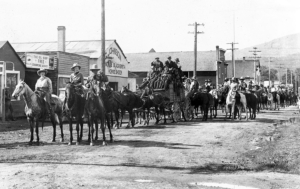

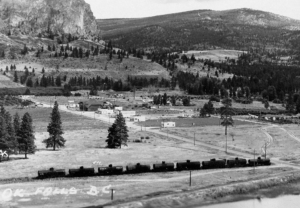

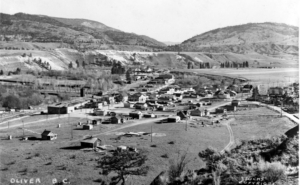

The humble beginnings of the town of Oliver – originally called “Canteen” 1922

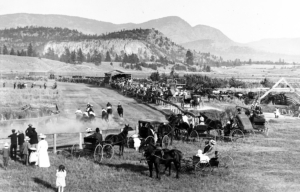

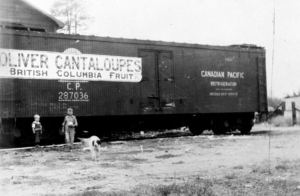

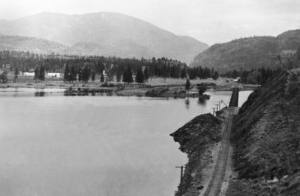

What this Act of the Legislature enabled Oliver to do, was to raise funds to purchase a parcel of land from Senator Lytton Shatford and the South Okanagan Land Company. A deal was drawn up for the purchase of 22,000 acres of land from the border to Okanagan Falls, along the Okanagan River. The price was $350,000. In 1919, the South Okanagan Lands Project was launched.

Lytton Shatford MLA and Senator

Returning veterans were given special purchasing privileges for the land to be developed. They could work on the water system for $5 for a 10 hour day and chose a five or ten acre parcel for 10% down of the $1000 (five acre) or $1000 (ten acre). Price per acre was half for the bigger parcel. If they made the payments for 5 years they would receive a $500 rebate. Irrigation rates would be an additional $6 per acre per year. A hundred and fifty men came for the first contract.

Oliver had already established himself as one of Brewster’s chief lieutenants when the premier died on March 1st, 1918. Oliver was elected leader of the Liberal party and on March 6th, he became premier. He would hold the reins of power, in his distinctively rustic fashion, for almost a decade. He was to retain the agriculture portfolio until April, 1918 and the railway portfolio until October, 1922.

When Oliver became premier, his government attempted to deal with the challenges anticipated in the post-war period by introducing social legislation that limited work to an eight-hour day in certain industries, improved working conditions, and provided a minimum wage for women. It moved as well to establish mothers’ pensions in 1920, to provide maintenance for deserted wives, and to improve both health and educational services. Legislation to regulate public utilities and impose controls on the forest industry was also passed.

In 1927, his greatest feat was the passing of the Old Age Pension Act. All of these initiatives were based on the belief that direct government intervention was the best way to deal with the problems that beset the province after the war.

While on tour in May of 1927, he fell ill and was rushed to Mayo clinic where it was discovered he had cancer. He died soon after.

That’s why Oliver is named in recognition of “Honest John” and his dedication to the province and to our veterans.

source: James Morton – Honest John Oliver,

J.M.Dent & Sons Ltd. – 1933

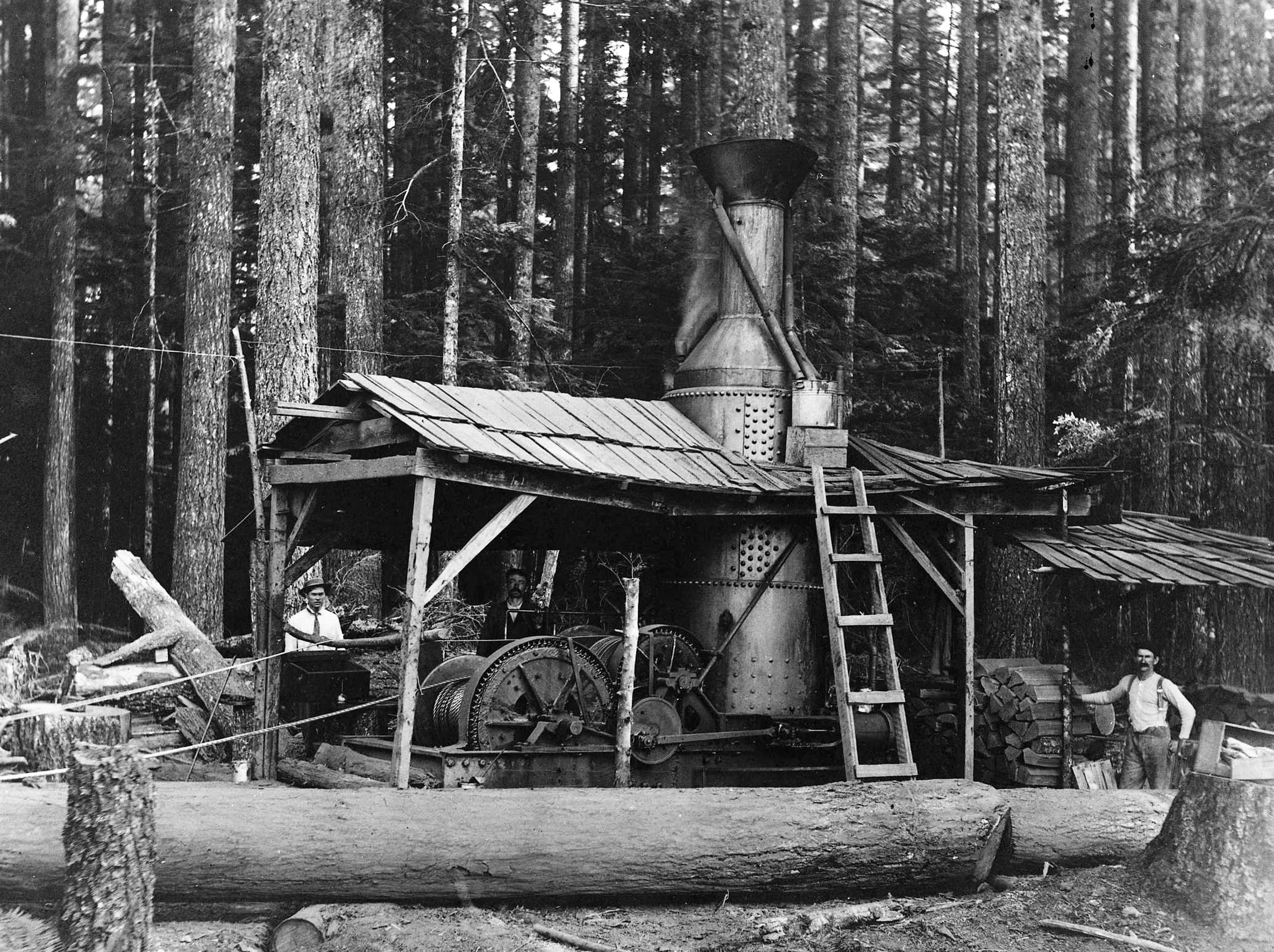

When I was a boy my father sometimes took me to watch the powerful logging machines at work. It really was an exciting experience to watch these steam engines pull these tree-length logs three to four feet in diameter through the woods. The men who operated these steam donkeys were masters of their art and as a boy, it was exciting to watch the men unloading these machines from the barges they brought them in on. They would move these big machines ahead on the barge until they were ready to tip over, then yank the throttle wide open and they would leap onto the beach. They would have a team of horses roll the cable from the first donkey out to its length and anchor to a tree. The others would attach their cable to the one ahead so when the first donkey pulled itself ahead, it would pull the cable of the second donkey out and then it would pull itself up to the first donkey and so on until they reached their work point. I think my greatest ambition as a boy was to be a donkey puncher, as the men who operated them were called. In the winter they used a lot of horses when logs could be hauled on the snow on large, two-runner sleighs, called sloops. The roads were watered to create ice roads so two horses could move large loads. They used another team called a snatch team to start the load moving

When I was a boy my father sometimes took me to watch the powerful logging machines at work. It really was an exciting experience to watch these steam engines pull these tree-length logs three to four feet in diameter through the woods. The men who operated these steam donkeys were masters of their art and as a boy, it was exciting to watch the men unloading these machines from the barges they brought them in on. They would move these big machines ahead on the barge until they were ready to tip over, then yank the throttle wide open and they would leap onto the beach. They would have a team of horses roll the cable from the first donkey out to its length and anchor to a tree. The others would attach their cable to the one ahead so when the first donkey pulled itself ahead, it would pull the cable of the second donkey out and then it would pull itself up to the first donkey and so on until they reached their work point. I think my greatest ambition as a boy was to be a donkey puncher, as the men who operated them were called. In the winter they used a lot of horses when logs could be hauled on the snow on large, two-runner sleighs, called sloops. The roads were watered to create ice roads so two horses could move large loads. They used another team called a snatch team to start the load moving  people: father, mother, and two sons, Carl and Guy.

people: father, mother, and two sons, Carl and Guy.  The original house was small and built from cedar logs stood on end on a wooden foundation. Some years later they built a two-storey addition more than twice the size of the original house and it was built on a cement foundation. In Guy’s last years he built another addition to the back of the newer part of the house. It was a beautiful billiard room. The family also had a large grand piano in the living room as both Mr. and Mrs. Collings were pianists. This large piano was built into the house so the only way it could be taken out would be to take it to pieces or take the end wall out of the living room. The living room also had a large home-made stone fireplace and a lot of ornaments that Mr. Collings had brought from various parts of the world. One of those was a music box that was gifted to the Collings from former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt. This amazing music box played the big huge steel discs, so when I would go over there the one song that the boys just loved to play was “Listen to a Mockingbird”. The huge steel things would play that in a trill that this music box made it sound so incredible it almost brought tears to your eyes.

The original house was small and built from cedar logs stood on end on a wooden foundation. Some years later they built a two-storey addition more than twice the size of the original house and it was built on a cement foundation. In Guy’s last years he built another addition to the back of the newer part of the house. It was a beautiful billiard room. The family also had a large grand piano in the living room as both Mr. and Mrs. Collings were pianists. This large piano was built into the house so the only way it could be taken out would be to take it to pieces or take the end wall out of the living room. The living room also had a large home-made stone fireplace and a lot of ornaments that Mr. Collings had brought from various parts of the world. One of those was a music box that was gifted to the Collings from former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt. This amazing music box played the big huge steel discs, so when I would go over there the one song that the boys just loved to play was “Listen to a Mockingbird”. The huge steel things would play that in a trill that this music box made it sound so incredible it almost brought tears to your eyes.

In the year 1900, the Canadian Pacific Railway made the decision to acquire 10,000 acres of land in the Interior of British Columbia to grow fruit for their new C.P.R. hotels. By 1901, after an extensive search, two properties were short-listed. The Kamloops proposal was dropped because of questionable water reliability. The Trout Creek property, in the centre of the Okanagan Valley, was also dropped because there wasn’t enough acreage; only 4,000 acres. So the C.P.R executive abandoned the idea. But C.P.R. President Sir Thomas Shaughnessy (1853-1923) decided to personally proceed with the acquisition of the Trout Creek property.

In the year 1900, the Canadian Pacific Railway made the decision to acquire 10,000 acres of land in the Interior of British Columbia to grow fruit for their new C.P.R. hotels. By 1901, after an extensive search, two properties were short-listed. The Kamloops proposal was dropped because of questionable water reliability. The Trout Creek property, in the centre of the Okanagan Valley, was also dropped because there wasn’t enough acreage; only 4,000 acres. So the C.P.R executive abandoned the idea. But C.P.R. President Sir Thomas Shaughnessy (1853-1923) decided to personally proceed with the acquisition of the Trout Creek property. Shaughnessy created the Summerland Syndicate to purchase Barclay’s Trout Creek cattle ranch. By August 1902 the sales agreement between George Barclay and the Summerland Syndicate was completed.

Shaughnessy created the Summerland Syndicate to purchase Barclay’s Trout Creek cattle ranch. By August 1902 the sales agreement between George Barclay and the Summerland Syndicate was completed. the water system, the road system, the electrical system (first community in the Okanagan) and his company assisted with the telephone system. Shaughnessy moved quickly. In the Fall of 1902, his company built the Summerland Hotel.

the water system, the road system, the electrical system (first community in the Okanagan) and his company assisted with the telephone system. Shaughnessy moved quickly. In the Fall of 1902, his company built the Summerland Hotel.

Son George Bell and Gordon Bell

Son George Bell and Gordon Bell Four giant cranes from the GWIL firm were on site setting up, and a check with the loadmaster revealed that Tuesday morning, April 20th, the lift was to start at 8am. However, Mr. Bell, who engineered the whole project, pointed out that one crane would have to be re-rigged as the lifts must be positioned 90 degrees apart. This was not the case. Re-rigging took place on one crane at 8:15 and by 9am the set-up was done. The lift started at 9:30 and all four cranes lifted in unison. By 10am it was obvious that this 53.5 ton roof section was starting to move in the breeze slightly and appeared to resemble a flying saucer. Streamer ropes attached to the roof were then tied onto vehicles on site as anchors and the motion was soon controlled.

Four giant cranes from the GWIL firm were on site setting up, and a check with the loadmaster revealed that Tuesday morning, April 20th, the lift was to start at 8am. However, Mr. Bell, who engineered the whole project, pointed out that one crane would have to be re-rigged as the lifts must be positioned 90 degrees apart. This was not the case. Re-rigging took place on one crane at 8:15 and by 9am the set-up was done. The lift started at 9:30 and all four cranes lifted in unison. By 10am it was obvious that this 53.5 ton roof section was starting to move in the breeze slightly and appeared to resemble a flying saucer. Streamer ropes attached to the roof were then tied onto vehicles on site as anchors and the motion was soon controlled. Gordon was on the roof of the museum building to receive and guide into place the new roof section. The alignment was perfect. The next step was to lift into place the remaining 24 “I” beams to support the roof section other than at the museum building proper. This task was completed by a local crane company who worked under the 53.5 ton roof section while the GWILL cranes maintained their lift. Finally by 15:30 the roof was lowered into place on the “I” beam columns. Welding the roof to the “I” beams was the next step while the GWIL cranes prepared to depart from their two-day task.

Gordon was on the roof of the museum building to receive and guide into place the new roof section. The alignment was perfect. The next step was to lift into place the remaining 24 “I” beams to support the roof section other than at the museum building proper. This task was completed by a local crane company who worked under the 53.5 ton roof section while the GWILL cranes maintained their lift. Finally by 15:30 the roof was lowered into place on the “I” beam columns. Welding the roof to the “I” beams was the next step while the GWIL cranes prepared to depart from their two-day task.

Princeton in 5 days over the well-marked pack trail.

Princeton in 5 days over the well-marked pack trail. Cascade for most of his life. He made a few dollars as a guide and packer for those travelling the trails from Hope. He had the survival skills of a native.

Cascade for most of his life. He made a few dollars as a guide and packer for those travelling the trails from Hope. He had the survival skills of a native. at the trailhead near Whipsaw Creek. Fred went ahead at this point and arranged a cart to be sent up to fetch her. Mrs. Barrington-Foote heard the news and insisted on coming along to help as only another woman could in this situation. She was taken to Princeton Hospital where she was tended to. She weighed in at just over 80 pounds.

at the trailhead near Whipsaw Creek. Fred went ahead at this point and arranged a cart to be sent up to fetch her. Mrs. Barrington-Foote heard the news and insisted on coming along to help as only another woman could in this situation. She was taken to Princeton Hospital where she was tended to. She weighed in at just over 80 pounds.