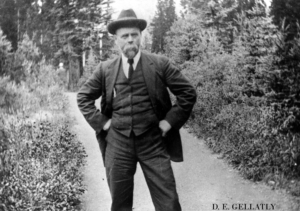

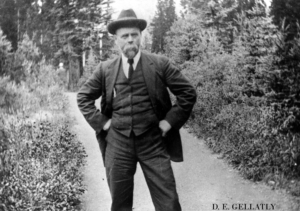

The Gellatly family comprised of David E., Eliza, and four sons and five daughters, arrived at Powers Creek near what was to become Westbank in 1900. They had worked hard growing potatoes at Shorts Creek across from Okanagan Landing and had earned enough to actually purchase their own parcel of rough, uncleared land close to a year-round creek.

All their efforts depended on the water rights to the creek, and Mr. Gellatly made it clear with his neighbours that he would hold the rights. This caused considerable strife, but also led to the establishment of the Okanagan Irrigation and Power Company Ltd. The company offered 100,000 shares at $1 each with funds raised going to improvements and dams on Powers Creek. The surrounding farmers protested that they were buying into a project that they already owned and so the company folded before it began. What this did establish was Mr. Gellatly’s dominance in the area.

All their efforts depended on the water rights to the creek, and Mr. Gellatly made it clear with his neighbours that he would hold the rights. This caused considerable strife, but also led to the establishment of the Okanagan Irrigation and Power Company Ltd. The company offered 100,000 shares at $1 each with funds raised going to improvements and dams on Powers Creek. The surrounding farmers protested that they were buying into a project that they already owned and so the company folded before it began. What this did establish was Mr. Gellatly’s dominance in the area.

The Gellatlys planted crops immediately after the land was cleared, both on the lower acres and on the benchlands. Onions, tomatoes, and squash were shipped east right away. By 1903, there were berries, peas, beans, and melons harvested from between the rows of young fruit trees.

Onions, tomatoes, and squash were shipped east right away. By 1903, there were berries, peas, beans, and melons harvested from between the rows of young fruit trees.

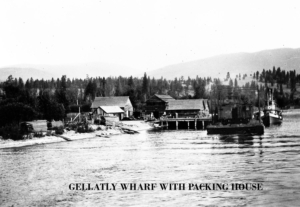

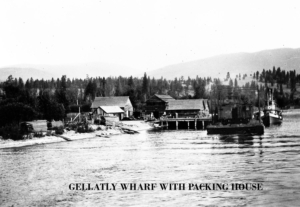

It wasn’t long before a steamer wharf was constructed, complete with packinghouse, warehouse, box factory and stables. D.E. Gellatly made application for a Post Office, and in July, 1903, the application was granted and “Gellatly” became a post office with D.E. as postmaster. He also applied to CPR to sell money orders and telegraphs, and became a “Station Agent.” He was an officer of several Kelowna banks and cashed cheques for the locals. Mr. Gellatly rented cold storage in the warehouse and brokered fruit sales from Peachland to Bear Creek. He was the quintessential “Tomato King” of the west side of the lake.

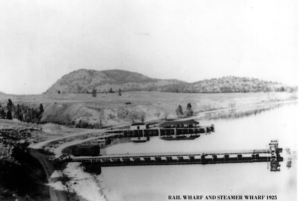

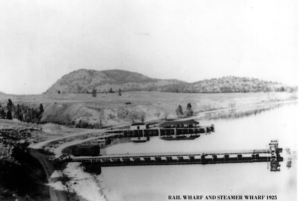

D.E. had always had problems with CPR. The Gellatly’s were, as all other growers, dependant on the good service of steamers and tugs. In 1908, with the financial assistance of the Provincial Government, D.E. Gellatly built a shipping wharf for Gellatly Landing. The Government provided the pilings and superstructure for the north side of the wharf, and Gellatlys built the buildings on the south portion.

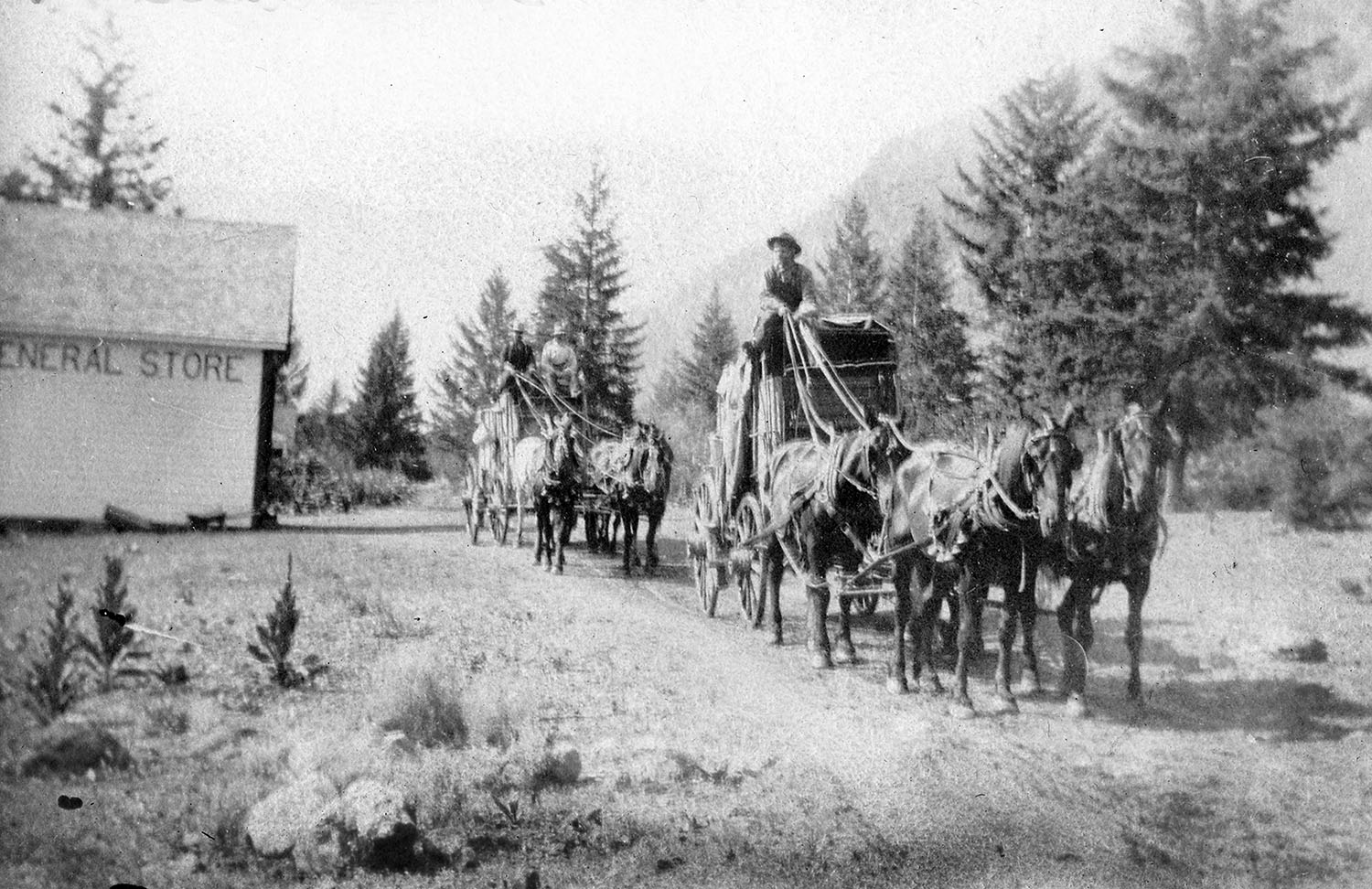

Even though the system was in place, it did not guarantee timely delivery. The system seemed simple enough. If you had between 3 and 5 tons of produce, you could load bushel boxes or sacks on the sternwheelers with handcarts. Each part of the shipment was delivered to a wharf or depot for pick up. If it was more than 10 tons you leased a freight car from CPR and loaded it yourself, then sealed it, and it would be unloaded by a broker in Calgary or Winnipeg, then delivered to the wholesalers. The hope was that the car would stay cool and dry and not sit on a siding for a week. CPR made you think it could deliver in 3 days.

Even though the system was in place, it did not guarantee timely delivery. The system seemed simple enough. If you had between 3 and 5 tons of produce, you could load bushel boxes or sacks on the sternwheelers with handcarts. Each part of the shipment was delivered to a wharf or depot for pick up. If it was more than 10 tons you leased a freight car from CPR and loaded it yourself, then sealed it, and it would be unloaded by a broker in Calgary or Winnipeg, then delivered to the wholesalers. The hope was that the car would stay cool and dry and not sit on a siding for a week. CPR made you think it could deliver in 3 days.

“City Health Department, Winnipeg, February 23, 1912.

Dear Mr. Gellatly,

Re: Inspection of Cars

The first car arrived on Sept. 18/11 and was seen by me on Sept. 25th and ordered re-packed. I also saw the car on Sept. 26th, 27th, October 2nd, 4th, and 5th, the ticket being given for condemned tomatoes on the 5th.

The second car arrived on Sept. 28th, was seen by me on the 29th, and visited on October 12th, 17th, 19th 20th, 21st, and 23rd, the ticket being given for condemned tomatoes on the 23rd.I looked these dates up in my daily reports. The large number of visits paid was for the purpose of seeing that the re-packing was properly done and only bad tomatoes destroyed.

Sincerely, P.B. Gustin, Chief of Food and Dairy Division”

By 1910, with all crops producing extremely well, David and Sons found a good Scottish distributor in Calgary. The MacPherson Fruit Company Ltd. appointed one of their brokers, Mr. J.G. Moody, to oversee the receiving and distribution of Okanagan produce to points north and east. Mr. Moody was incredibly successful in selling anything Gellatly farms could produce.

On the night of October 20th, 1910, daughter Eliza died of scarlet fever. David and Mrs. Gellatly tried in vain to get medicine from Kelowna on to the sternwheeler using Dominion Express. It all went horribly wrong with the druggist missing the deadline for freight. Mr. Gellatly took quick action to hold all responsible with written complaints and legal letters to CPR, Dominion Express, Willit’s Drugs, and Dr. Knox. The loss was devastating and it changed the way the family dealt with CPR. There was a trust that was broken.

“Scott Fruit Company, Medicine Hat January 13th, 1915

Gentlemen,

We beg to draw your attention to 6 sacks of onions over-credited in car #92014, these we have applied on car #72016 and paid for one which balances the 7 short on the latter car.

There was heavy loss by shrinkage on cukes, cants, citron, & tomatoes as shown on the statements, but apart from these items we think we have done very well for you.

Regarding the freight on that car, we took the matter up with CPR and they showed that the words “to make up a minimum car” was a mistake, it should have been “to make up actual weight as scaled at Calgary.” We have to pay the net weight according to the CPR’s scaling and if a car is billed at less than the scaled weight, the CPR adds the difference.”

D.E. made a dramatic change to operations in 1915, with the incorporation of the British Columbia Fruit and Produce Company Ltd. He leased the empty Massey-Harris tractor warehouse next to the rail yards in Calgary as a distribution point for his goods. He put J.G. Moody in charge, hired workers, and installed cold storage units. This proved successful and was a banner year for sales.

At home, the S.S. Sicamous and tug Naramata had been launched on Okanagan Lake the year before. CPR was installing car-slips (wharfs with rails) at some of the larger centres to allow barges to unload boxcars and leave them while serving other areas. Gellatly immediately made application for one of the car-slips.

“To: F.W. Peters, Department of Transport

June 19/15

Sir:

For your information, I can say that we had commenced the grading of the trackage and had all our arrangements for rails and other materials completed. When Captain Gore, acting under instructions from Mr. McKay, called and asked us to suspend operations for the purpose of allowing the company a chance to include a carslip in the next appropriations, and stating that in consideration of our doing so that he would arrange for a car-barge service so that we could load the cars on the barge. This arrangement was carried out satisfactorily (as in the past).

But conditions are so very much changed that it would be impossible to handle crops of Westbank and our own under the present arrangements……trusting that you will go into this matter fully and investigate conditions before coming to the conclusion that the carslip would only serve us individually. You will find that the Westbank District is also interested in having the carslip built.”

On July 31st, 1915, D.E. Gellatly wrote to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works in Victoria:

“Sir:

We beg to make application for the cancellation of lease of the foreshore rights granted to the CPR in 1908 at Gellatly for a car-slip.

Owing to the failure of the company to construct or provide any shipping facilities for the handling of car load shipments, makes it necessary for us to have car-slip accommodation which we are willing to construct at our own expense. But we are unable to do so owing to the most available and suitable site being held by the CPR.”

The reply was:

“After careful consideration of the case as submitted by the Railway Company, this department is of the opinion that it will not be possible to entertain your application for the cancellation of the lease in question. Before the lease was given, your consent appears to have been secured and you doubtless entered into some satisfactory arrangement with the railway company as to the matter in which the said premises should be improved and used.”

Gellatly Farms and the surrounding orchardists were forced to continue loading at wharves, both Gellatly and Westbank, the old way by hand rather on carslips. This went on until 1919.

In the spring of 1919, Captain Robertson of the S.S. Sicamous started making beach landings at Gellatly. His decision was made on inspection of the condition of the wharf. David protested loudly. He now had to haul goods to the Westbank wharf about a mile from Gellatly. He continued to correspond with the Province to fund the upgrade of their portion of his wharf.

“Sir:

During the many years that Capt. Estabrooks was on the steamers, the wharves were never in the condition that they are in at present, and the cause is not far to seek, even our slip protected by a pile many feet distance from the wharf was demolished, track and all. We must insist on the steamer making landings at the wharf during suitable weather conditions. It is no more difficult to land at the wharf than at the point (beach landing) during a south wind, and now that there is high water there is ample room to make the landing on the part of the wharf that is not damaged.”

Then on October 28, 1919, the S.S. Sicamous rammed the wharf at Gellatly, destroying the front portion and nearly injuring those waiting to board. The family set to repairs at their own expense. Frustration was wearing D.E. Gellatly thin.

His efforts now focused on the planned construction of a central wharf to be built half way between the Government Wharf at Westbank and Gellatly Wharf. A petition had been circulated 2 years ago and had remained on the provincial minister’s desk with no mention of deliberation. The excuse was negotiations with the Dominion Government.

It was assumed that one of the landings had to go. It was to be Gellatly.

The protest was launched:

“Minister of Transportation, November 10th, 1919

Sir: (excerpt)

For your information to the Department –

In reference to the wharf at Westbank: This wharf is built on the Indian Reserve and the Indians refuse to allow any buildings to be erected for the storage of shipments thereby rendering it impossible to ship perishable products during the winter months.

Owing to these restrictions, it is necessary that a wharf be constructed where building sites can be secured for the necessary warehouse accommodation. A suitable site has been offered. The attached plan shows a site in the bay about half way between the two wharves, which adjoins the Government roads from Westbank, Gellatly and Glenrosa. This would meet the requirements of the whole district as a shipping point.”

And finally:

“From Jas Burray, CPR, Okanagan Landing, December 29, 1919

Dear Sir:

In order to assist you in moving your produce this winter, it will be in order for you to flag the steamer Sicamous northbound only, three times a week providing you have not less than five tons or more to move, if you have southbound shipments to go forward, you may put them on the stop northbound and we will deliver same at destination on the south trip. The calls of course will be subject to weather conditions and wharf condition.”

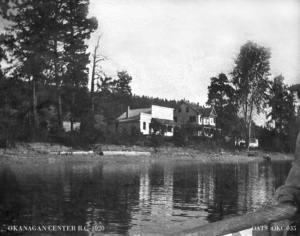

The wharf at Gellatly got worse as the community grew. There was a tremendous need for suitable freighting slips and other communities were getting them. CPR launched a second tug “Kelowna” in 1920 and proceeded to build barge slips at Summerland, Okanagan Centre and even Greata Ranch. There was talk of the Canadian Northern Railway being built from Kamloops to Kelowna. Westbank and Gellatly were not included in any of these plans.

The Calgary office just couldn’t fill orders with all these shipping delays. The family decided to just sell what they could locally and close the warehouse. They were able to sublet the building to the C.P.R. Soon after, the British Columbia Fruit and Produce Company Ltd. was dissolved.

Disaster struck the Gellatly Family. March 3rd, 1920, the wharf and all its buildings burned to the water line. It was thought that a spark from the stack of the S.S. Sicamous had landed on the roof of the warehouse setting it ablaze. There was some insurance in the amount of $4000 but the losses were over $20,000

David Sr. accused CPR of negligence and immediately retained E.P. Davis, a Vancouver lawyer, to begin a suit for $25,000 and costs. CPR Lawyer J.E McMullen answered with “The Company is quite satisfied the fire was not caused by sparks from the Steamer “Sicamous”.

quite satisfied the fire was not caused by sparks from the Steamer “Sicamous”.

Gellatly was told that this accusation was going to be very difficult to prove in court. David set out to garner proof himself with testimonials from those who were there.

“To: Robert Pearson, Esq., Vancouver B.C.

April 6/20

Dear Sir: Having had our wharf and buildings burned down on the 3rd of March from a spark from the steamer setting the roof of the packing shed on fire while loading a car of apples here. We intend bringing suit against the Canadian Pacific Railway Co. for the amount of our loss and wish to have all the evidence possible to prove our case. Knowing that you have been on the steamer for some considerable time, we thought you could possibly help to prove that sparks or hot ashes come from the smoke stack. The writer went on the top deck today and noticed considerable fine ashes in the lifeboats which evidently came from the funnel. Kindly let us know all the particulars in this connection.”

The insurance company sent an adjuster to view the damage. Even though D.E. had let the policy run out, the claim was processed and sometime later a cheque was received. After legal fees demanded were paid, little was left for the rebuilding of the wharf. Application was made to the Provincial Government for funds to rebuild but as only a portion of the wharf was the responsibility of the province, the application was denied. He tried the Federal Government. They responded with: “As you know, the department already has a wharf at Westbank on which authority was given to expend this year the sum of $3300 and an additional item for the extension of the wharf is being noted for the consideration of Council in connection with the estimates for the fiscal year 1921-22.”

David Gellatly was dumb-struck. He was looking at more than two years before a court date and the CPR was playing their usual dirty tricks. Writs were not processed on time, witnesses were not told proper dates, postponements were often set without lawyers attending, and his lawyers wanted more money.

Then the final straw, the Inspector of Taxation wanted to audit the Calgary business. D.E. replied, “The British Columbia Fruit and Produce Company Ltd. was closed up over a year ago with a liability of over $10,000. The books and papers were shipped here some time in February and reached here on March 2nd. Unfortunately they were in our warehouses on March 3rd when the whole premises were destroyed by fire causing a loss of $34,000.”

The lawsuit was never settled. David Erskine Gellatly was a broken man financially, emotionally and physically. He entered Vernon Jubilee Hospital for surgery from which he did not recover, dying on March 7th, 1920, at age 65.

Long Live the “Tomato King of the Okanagan”.

Authors note:

The Westbank carslip was installed not long after the launch of the CN #3 tug. It was begun in 1927 and completed October 1930. Rails installed to the packinghouse were used by both CPR and CNR until the 1970’s. The remnants of the wharf are now part of the lakeshore park swimming area.

Thank you to the Regional District of the Central Okanagan and the Gellatly Nut Farm Regional Park Society for the use of the comprehensive archive of the Gellatly family.

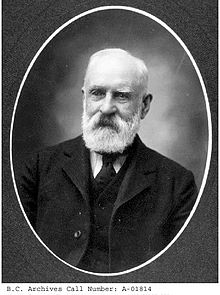

Walter Moberly was one of the great builders in B.C. History, and he ranks with explorers like Alexander MacKenzie, and David Thompson. He participated in two great achievements in the early development of British Columbia. These were the construction of the Cariboo road and the survey for an overland railway across British North America.

Walter Moberly was one of the great builders in B.C. History, and he ranks with explorers like Alexander MacKenzie, and David Thompson. He participated in two great achievements in the early development of British Columbia. These were the construction of the Cariboo road and the survey for an overland railway across British North America.

The idea of a rail route across the mountains remained his fixed purpose. So, in 1864, he handed over his department to J.W. Trutch and laid plans for the task ahead. Several routes seemed possible, but all appeared to be difficult and expensive. The first of these choices was by way of the Fraser Canyon, the North Thompson River, via Yellowhead Pass to Edmonton. This was felt to be too far north and would perhaps permit the southern part of the country to fall into the orbit of the United States. A second route that seemed a possibility was by way of the Fraser River and the South Thompson, then by a maze of canyons to the Columbia and the Great Bend, then to the Blueberry River and Howse Pass across the Rockies. A third route was by another series of canyons through the high Selkirks to the Kicking Horse Pass.

The idea of a rail route across the mountains remained his fixed purpose. So, in 1864, he handed over his department to J.W. Trutch and laid plans for the task ahead. Several routes seemed possible, but all appeared to be difficult and expensive. The first of these choices was by way of the Fraser Canyon, the North Thompson River, via Yellowhead Pass to Edmonton. This was felt to be too far north and would perhaps permit the southern part of the country to fall into the orbit of the United States. A second route that seemed a possibility was by way of the Fraser River and the South Thompson, then by a maze of canyons to the Columbia and the Great Bend, then to the Blueberry River and Howse Pass across the Rockies. A third route was by another series of canyons through the high Selkirks to the Kicking Horse Pass. Moberly favored the Big Bend of the Columbia route to Howse Pass. Under difficult weather conditions Gillette completed his examination and reported that a good line, though steep, could be made through Howse Pass. His surveys could not be completed because of snowstorms and they were forced to withdraw to winter quarters at Boat Encampment on the Columbia. This report confirmed Moberly’s opinion that it was a practical route. He had crossed the pass earlier that season to meet his brother, Frank, who was surveying on the Alberta slopes of the Rockies.

Moberly favored the Big Bend of the Columbia route to Howse Pass. Under difficult weather conditions Gillette completed his examination and reported that a good line, though steep, could be made through Howse Pass. His surveys could not be completed because of snowstorms and they were forced to withdraw to winter quarters at Boat Encampment on the Columbia. This report confirmed Moberly’s opinion that it was a practical route. He had crossed the pass earlier that season to meet his brother, Frank, who was surveying on the Alberta slopes of the Rockies.

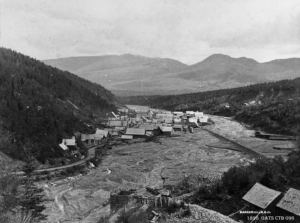

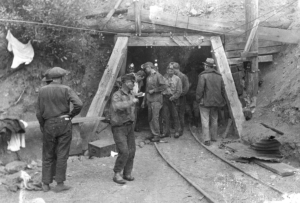

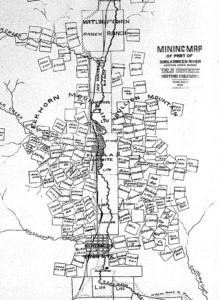

Coal is everywhere on the mountains in the Tulameen Valley. The veins of anthracite to the southwest of Coalmont are some of the best in the world and with the completion of the Kettle Valley railway in 1915 this coal could be shipped throughout the world.

Coal is everywhere on the mountains in the Tulameen Valley. The veins of anthracite to the southwest of Coalmont are some of the best in the world and with the completion of the Kettle Valley railway in 1915 this coal could be shipped throughout the world.

An essay by Brian Wilson ©2013

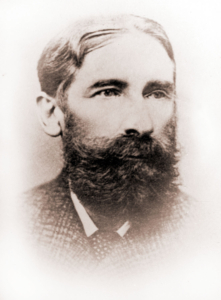

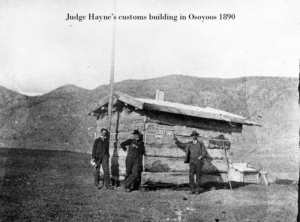

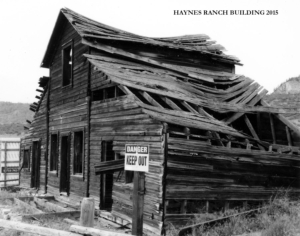

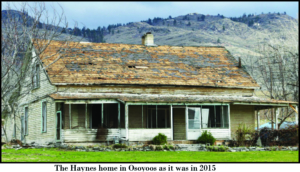

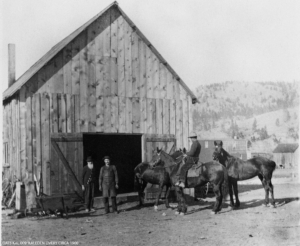

An essay by Brian Wilson ©2013 to which he added an adjoining 480-acre tract the following year. In 1872, Lowe suffered a severe accident when hit by a train in Ontario. He returned to BC, but completed his duties in New Westminster until his death in 1882. At this time, Haynes had to deal with Mrs. Lowe and she demanded a considerable sum of money for her interest in the Haynes ranch. It was decided to place a mortgage on the property through the British Land and Investment Company in New Westminster. Further acquisitions between 1874 and 1888 increased his holdings to 20,756 acres. He established a horse ranch but could not find a market, and turned to cattle ranching, eventually increasing his herd to 4,000 head and acquiring the title of “The Cattle-King of the South Okanagan.” With his long-time friend and fellow Irishman, Tom Ellis, he made cattle drives over the Hope Trail to New Westminster and over the Dewdney Trail to Kootenay and Calgary. With his fine house on the shores of Osoyoos Lake, it was rumoured that his properties had a value of $200,000. Doubtless all would have been well if the Judge had lived to manage his affairs.

to which he added an adjoining 480-acre tract the following year. In 1872, Lowe suffered a severe accident when hit by a train in Ontario. He returned to BC, but completed his duties in New Westminster until his death in 1882. At this time, Haynes had to deal with Mrs. Lowe and she demanded a considerable sum of money for her interest in the Haynes ranch. It was decided to place a mortgage on the property through the British Land and Investment Company in New Westminster. Further acquisitions between 1874 and 1888 increased his holdings to 20,756 acres. He established a horse ranch but could not find a market, and turned to cattle ranching, eventually increasing his herd to 4,000 head and acquiring the title of “The Cattle-King of the South Okanagan.” With his long-time friend and fellow Irishman, Tom Ellis, he made cattle drives over the Hope Trail to New Westminster and over the Dewdney Trail to Kootenay and Calgary. With his fine house on the shores of Osoyoos Lake, it was rumoured that his properties had a value of $200,000. Doubtless all would have been well if the Judge had lived to manage his affairs.

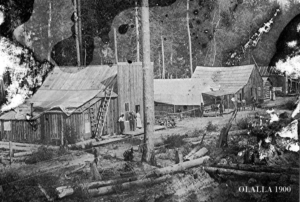

James Riorden was a rancher from Olalla. He was also one of the original 18 men who staked claims at Hedley Camp in 1895. Today, a mountain at Apex Alpine area is named in his honor.

James Riorden was a rancher from Olalla. He was also one of the original 18 men who staked claims at Hedley Camp in 1895. Today, a mountain at Apex Alpine area is named in his honor.

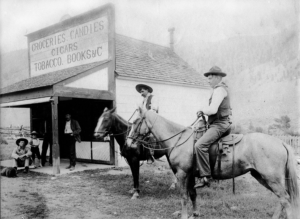

Keremeos farmer, opened a store in 1900. Soon after he became postmaster as well. Local rancher,

Keremeos farmer, opened a store in 1900. Soon after he became postmaster as well. Local rancher,

Water Street is aptly named as it was the high water mark of the era prior to drainage controls.

Water Street is aptly named as it was the high water mark of the era prior to drainage controls. year, the first Regatta was held.

year, the first Regatta was held. It wasn’t until after the war that the first parade was held. As with Penticton, the first was 1947 and it was a tremendous success. The Kinsmen Club and later the JCs organized a real crowd pleaser.

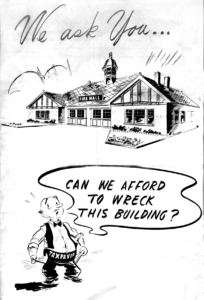

It wasn’t until after the war that the first parade was held. As with Penticton, the first was 1947 and it was a tremendous success. The Kinsmen Club and later the JCs organized a real crowd pleaser.  Association and the city. It was decided to not rebuild it and to change the theme of Regatta away from a community event to a tourist draw.

Association and the city. It was decided to not rebuild it and to change the theme of Regatta away from a community event to a tourist draw. competitor in downhill skiing. These were the champions raised in the pool at the Aquatic.

competitor in downhill skiing. These were the champions raised in the pool at the Aquatic.

Al and Evans Lougheed

Al and Evans Lougheed The old city building, magistrate’s office, police station and fire hall occupied 7 lots on that corner. Mayor Rathbun and his council were thrilled that a hotel could be built in the downtown core and he personally lobbied on the Lougheeds’ behalf to see them secure this property. The company offered $30,500 for the property. Seemed a little low at the time but the hotel would supply many jobs and services needed in the growing economy. As always seems to happen in Penticton, there was a tremendous outcry from some established citizens.

The old city building, magistrate’s office, police station and fire hall occupied 7 lots on that corner. Mayor Rathbun and his council were thrilled that a hotel could be built in the downtown core and he personally lobbied on the Lougheeds’ behalf to see them secure this property. The company offered $30,500 for the property. Seemed a little low at the time but the hotel would supply many jobs and services needed in the growing economy. As always seems to happen in Penticton, there was a tremendous outcry from some established citizens.

The building opened April 12th, 1957 to headlines of “Lougheed Brothers faith in city future typified in new building” and “Business services are boosted by Lougheed Block development.

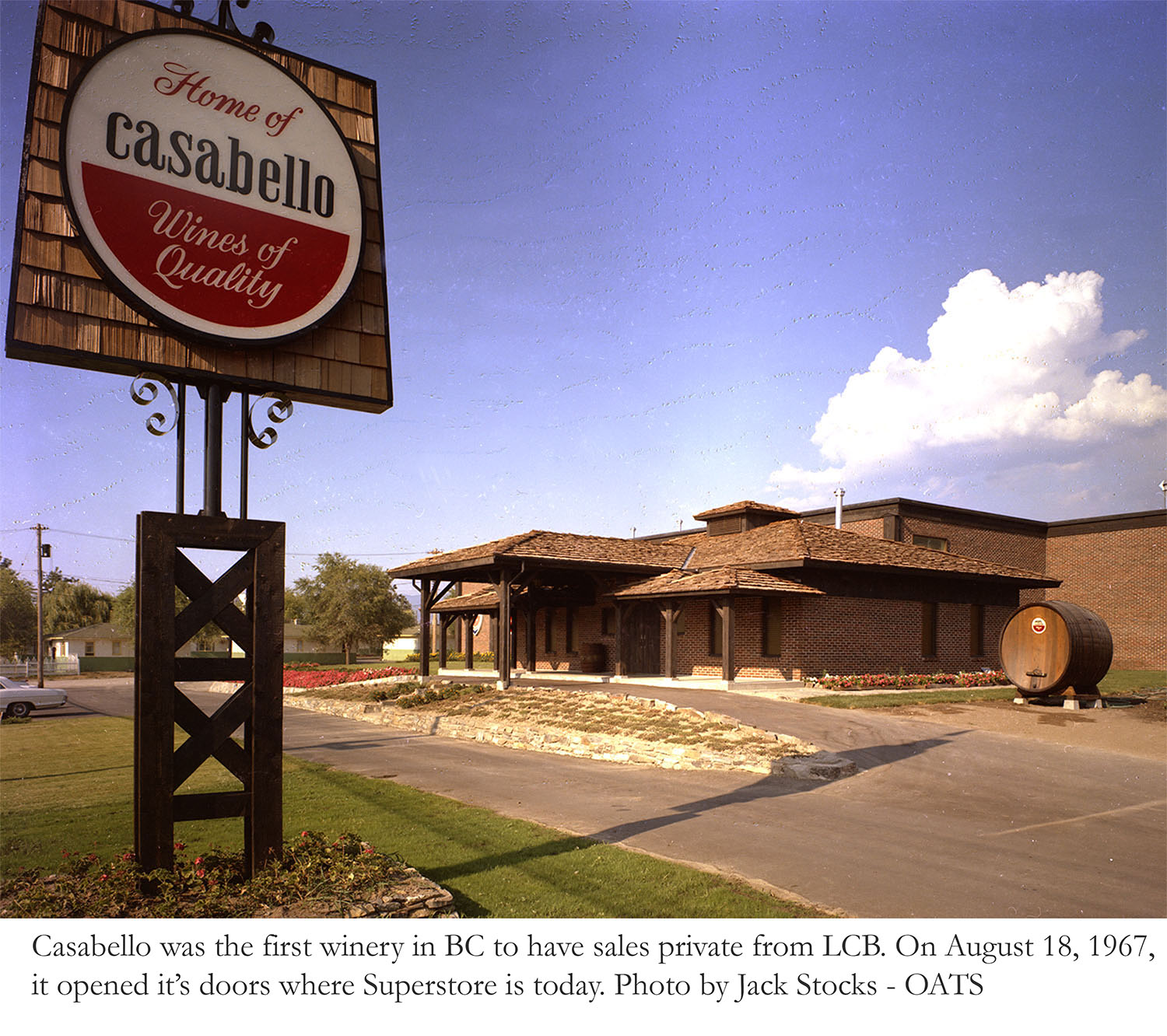

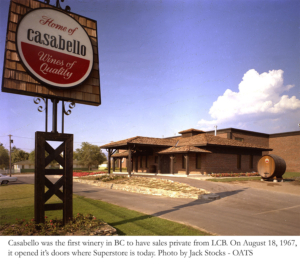

The building opened April 12th, 1957 to headlines of “Lougheed Brothers faith in city future typified in new building” and “Business services are boosted by Lougheed Block development. In 1964, the brothers sold the hotel and dissolved their business partnership. Al moved to Kelowna and invested in Haug Building Supply on Highway 97 near the corner of Highway 33. Evans stayed in Penticton and looked to the wine industry for a new enterprise.

In 1964, the brothers sold the hotel and dissolved their business partnership. Al moved to Kelowna and invested in Haug Building Supply on Highway 97 near the corner of Highway 33. Evans stayed in Penticton and looked to the wine industry for a new enterprise.

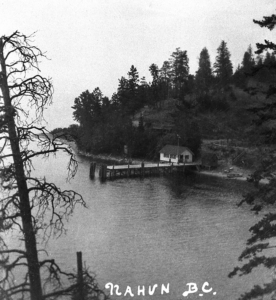

To give you a brief rundown on this most unusual gentleman, Old Kennard came to Canada from England well before the turn of the century and lived for many years at Nahun, on Okanagan Lake’s westside trail to O’Keefe Ranch. During his tenure, he kept a store and post office (he was the official Postmaster) that tended to about 40 people in the area.

To give you a brief rundown on this most unusual gentleman, Old Kennard came to Canada from England well before the turn of the century and lived for many years at Nahun, on Okanagan Lake’s westside trail to O’Keefe Ranch. During his tenure, he kept a store and post office (he was the official Postmaster) that tended to about 40 people in the area.

depression, after all.

depression, after all.

All their efforts depended on the water rights to the creek, and Mr. Gellatly made it clear with his neighbours that he would hold the rights. This caused considerable strife, but also led to the establishment of the Okanagan Irrigation and Power Company Ltd. The company offered 100,000 shares at $1 each with funds raised going to improvements and dams on Powers Creek. The surrounding farmers protested that they were buying into a project that they already owned and so the company folded before it began. What this did establish was Mr. Gellatly’s dominance in the area.

All their efforts depended on the water rights to the creek, and Mr. Gellatly made it clear with his neighbours that he would hold the rights. This caused considerable strife, but also led to the establishment of the Okanagan Irrigation and Power Company Ltd. The company offered 100,000 shares at $1 each with funds raised going to improvements and dams on Powers Creek. The surrounding farmers protested that they were buying into a project that they already owned and so the company folded before it began. What this did establish was Mr. Gellatly’s dominance in the area. Onions, tomatoes, and squash were shipped east right away. By 1903, there were berries, peas, beans, and melons harvested from between the rows of young fruit trees.

Onions, tomatoes, and squash were shipped east right away. By 1903, there were berries, peas, beans, and melons harvested from between the rows of young fruit trees. Even though the system was in place, it did not guarantee timely delivery. The system seemed simple enough. If you had between 3 and 5 tons of produce, you could load bushel boxes or sacks on the sternwheelers with handcarts. Each part of the shipment was delivered to a wharf or depot for pick up. If it was more than 10 tons you leased a freight car from CPR and loaded it yourself, then sealed it, and it would be unloaded by a broker in Calgary or Winnipeg, then delivered to the wholesalers. The hope was that the car would stay cool and dry and not sit on a siding for a week. CPR made you think it could deliver in 3 days.

Even though the system was in place, it did not guarantee timely delivery. The system seemed simple enough. If you had between 3 and 5 tons of produce, you could load bushel boxes or sacks on the sternwheelers with handcarts. Each part of the shipment was delivered to a wharf or depot for pick up. If it was more than 10 tons you leased a freight car from CPR and loaded it yourself, then sealed it, and it would be unloaded by a broker in Calgary or Winnipeg, then delivered to the wholesalers. The hope was that the car would stay cool and dry and not sit on a siding for a week. CPR made you think it could deliver in 3 days.

quite satisfied the fire was not caused by sparks from the Steamer “Sicamous”.

quite satisfied the fire was not caused by sparks from the Steamer “Sicamous”.

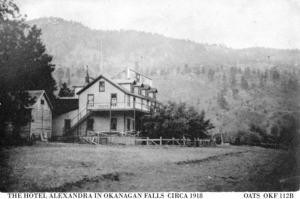

Many of the rooms faced north, offering a vista of the blue waters of the lake, nestled between grey-green hills that faded in the distance into the blue summer haze. The furnishings were lavish, in keeping with the anticipated development around the Falls and with the boom that extended across British Columbia.”

Many of the rooms faced north, offering a vista of the blue waters of the lake, nestled between grey-green hills that faded in the distance into the blue summer haze. The furnishings were lavish, in keeping with the anticipated development around the Falls and with the boom that extended across British Columbia.”

Within days of his return, he married Ellen Bassett, who he had courted prior to the war.

Within days of his return, he married Ellen Bassett, who he had courted prior to the war.