an essay by Brian Wilson with assistance of David Gregory

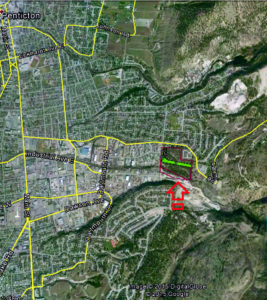

I think there is a story to be told of the disappearance of Indian Reserve No. 2. It seems to have been cut back between 1900 and 1906, and is a shadow of it’s previous mass.

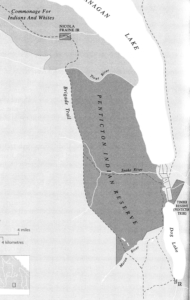

GREEN’S MAP 1897

GREEN’S MAP 1897Let’s do a little digging into the past: William G. Cox began his duties to Governor Douglas as magistrate of Rock Creek, and 1861 he had to deal with an uprising of miners and Natives. It seems a miner named Cherbart had been murdered by a young native of the Colville band. Although Cox had no jurisdiction on the U.S. side of the border, the young man was retrieved and subsequently hanged without trial. The Okanagans, led by Chief Silhitza protested the lynching by the American miners and the fact that Cox was powerless to charge the whites with any crime. Silhitza travelled to the Oblate Mission on Mission Creek and had the Priest write a letter to Governor Douglas outlining the out-of-control violence against Natives in the Okanagan. He writes “that is what rouses the anger of all the Okanagan tribe which has already taken up arms. I tried to quiet the insurrection by assuring them that I have recourse to your kindness, persuaded as I am that you will give Mr. Cox instructions on the subject.” When questioned by Douglas, Cox just shrugged it off, reporting that everything was “satisfactory”. The shooting and lynching continued and native life was changed forever.

Cox was not finished with the Okanagans having to report many more violent problems over two years. In every case the final outcome was frontier justice. Cox failed to have any effect on relations with natives and whites. Douglas finally took him away from the magistrate job and made him Assistant Commissioner of Lands and Works, answering to Colonel Moody. Cox then reported to the north of Okanagan Lake to deal with an armed insurrection of natives against miners. Moody charged him with marking out a “reserve” as defined by the Indians themselves. Cox had a lengthy interview with Chief Silhitza which ended in a satisfactory agreement for a reserve encompassing most of the head of the lake from Swan Lake to the Kamloops trail. Cox was sent off to do the same for the other Tribes of the Okanagan Nation.

Silhitza drew up a reserve for himself in N’kwala (Nicola Valley) and moved off hoping all was well. But then disaster struck. The Okanagans were decimated by a small pox outbreak in 1862/63. The many deaths seriously affected the population and their ability to govern themselves and it wasn’t long before white settlers began gnawing away at the reserves.

John Carmichael Haynes replaced W. G. Cox as the Queen’s representative in the Okanagan Valley in 1862. Haynes was appointed to the Legislative Council in 1864 and commissioned as a Justice of the Peace as well as Collector of Customs. From his office in New Westminster he dealt with numerous complaints from good British immigrants. They complained that the Natives of the Okanagan had garnered all the best agricultural land and weren’t using it for anything but grazing. Haynes agreed that the reserves were far too large for the diminished population and he would authorize disposal of lands with compensation. Colonial Secretary Birch stepped into the fray and ordered Haynes to dispossess the Indians without compensation as the reserves were “out of proportion”.

Haynes was given an awesome level of power to deal with all issues of government in the south interior, near lordly, somewhat medieval. Judge Haynes arrived via the newly completed Dewdney Trail in 1865 to meet with surveyor J. Turnbull. They met with Chief Tonasket and travelled to Penticton to see Tom Ellis, local cattle rancher. Turnbull did his best to map out the new boundaries as instructed by Haynes and to the disgust of Chief Tonasket. Tonasket can be credited for the retention of the best bottom lands for the Bands but the reserves on the lake were reduced to a shadow of the former acreage and common grazing lands were removed completely.

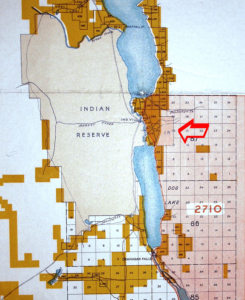

SPROAT MAP 1877

The Okanagans rose up in discontent until armed rebellion was imminent. Their case impossible to ignore. Haynes’ reserves proved unworkable and were never gazetted.

Gilbert Sproat was named sole commissioner of the Joint Indian Reserve Commission in 1877, and in his short tenure (1880) he layed out the reserves for the Okanagan Tribes, based on the inherent need for grazing, fishing and forestry.

It seems at this point that Penticton Indian Band along with other bands in the valley were satisfied with the results. Penticton claimed five reserves: the west side reserve No. 1, the forest reserve No. 2, the Summerland reserve No. 3, the grazing reserve No. 4 and the Okanagan Falls fishing reserve No. 5.

My research shows that Tom Ellis would not have any of it. Ellis, along with Haynes and his railway syndicate to the south, depended on the grazing of cattle from Okanagan Mountain to the border. Reserve No. 2 lands were claimed by them.

As related in her book, Kathleen Ellis writes that her father proceeded to fence the “east benches”. There would have been only one reason to invest in a fence of this magnitude and that was to diminish the claims of the Penticton Band. Right or wrong he moved to keep them out.

Judge Haynes died in 1888 and Ellis purchased the Haynes estate. It was important to keep it all intact to satisfy the investment syndicate.

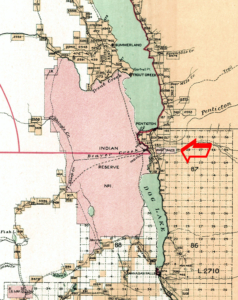

Green’s Map of 1906 above shows clearly just how little of Reserve No. 2 remained. Originally Reserve No. 2 comprised 1,427 acres and Ellis took 1,107 of them. This map was produced one year after Ellis sold all his holdings to Okanagan MLA Lytton Shatford and his three brothers.

The Shatfords immediately began selling farming lots and ranches to British immigrants and remittance men at huge profits.

Lytton Shatford’s Southern Okanagan Land Co. lobbied the McKenna-McBride Commission in 1916 to have the remaining 320 acres of Reserve No.2 deleted and reverted to the Crown. There are few records from that era to confirm this research.

In 1982, Penticton Indian Band was compensated $14.2 million for some of the loss.

This article contains research readily available in public archives.