It seems that in the spring of 1882, Bob Sproule and a couple of fellow prospectors left Bonner’s Ferry, Idaho for a look up Kootenay Lake. They went with the current in a small rowboat to check the rock outcrops of the east shore. There had been documented reports of low-grade outcrops here since David Douglas, the botanist, reported it in 1825, and Senator George Hearst visited in 1864.

To re-establish the claim, Sproule would have to travel 240 miles to Wild Horse Creek, near Fernie, to the registrar of mines office. He planned to be away a mere 72 hours.

Just as Sproule left for Wild Horse, another prospector entered the scene. Tom Hammill was an employee of the Ainsworth Mining Railway Company out of Portland, Oregon. They had a camp and mine in it’s infancy just across the lake. Hammill had a huge advantage of being accompanied by the current gold commissioner and Justice of the Peace, Judge J.C. Haynes. Hammill registered the claim on the spot. He waited the obligatory 72 hours, picked up his tools and began working.

Sproule arrived back to find Hammill well set in his mine. Sproule headed for Nelson to begin a court battle to regain possession of his claim. He succeeded but the court costs were more than he or his supporters could handle. The court seized the claim and the sheriff sold it for the court. Hammill was able to purchase it for a song and took legal possession soon after.

Sproule could not accept the verdict and haunted Hammill at the mine. One evening, he drew a bead on Hammill and shot him dead.

A posse from Nelson hunted Sproule for weeks in the mountainous wilderness until he was apprehended trying to cross the border near Creston. He was tried and subsequently hanged for his crime.

But wait, that’s not the whole story. There are several sidebars to this tale.

We have to look at the naming of Gray Creek. There are two candidates for its namesake: prospector/rancher Alden Samuel Gray (1849-1942) and surveyor/engineer John Hamilton Gray (1853-1941). The latter’s father, also named John Hamilton Gray, was the second premier of New Brunswick prior to confederation, as well as a judge.

By strange coincidence, he was one of two unrelated Fathers of Confederation named John Hamilton Gray. The other was premier of Prince Edward Island when the Charlottetown Conference that led to Canada’s birth was held in 1864.

Research notes both were often referred to as Colonel Gray — the PEI Gray, because he was a retired officer with the British Dragoon Guards, and the New Brunswick Gray, because he held the rank of lieutenant-colonel with the New Brunswick militia. Both were also strong supporters of confederation.

The New Brunswick Gray moved to Victoria in 1872 when he was named a judge of the Supreme Court of BC, a position he held until his death in 1889.

His appointment was criticized by many, including chief justice Matthew Begbie, who felt another judge was not needed. According to historian Margaret Ormsby, the judgeship may have been a consolation prize after Gray was passed over for speaker of the House of Commons. His grave is in Ross Bay Cemetery in Victoria, making him the only Father of Confederation buried west of Ontario.

Back to Sproule’s court case. It’s not well known that Gray was the presiding judge when Robert Sproule was tried in Victoria for the murder of Thomas Hammill.

A jury convicted Sproule of murder and Judge Gray, whose questionable advice seemed to ensure the guilty verdict, sentenced him to hang.

“One of the criticisms of Judge Gray is that he seemed overly interested in the details of Sproule’s capture,” Nelson Star says, “perhaps thinking it was destiny or God’s will that Sproule be caught, which made him guiltier in the eyes of the judge.”

Following several reprieves, Sproule was executed in Victoria, the likely victim of a miscarriage of justice.

THE BLUEBELL MINE BLOSSOMS

The Ainsworth group lost their interest in the mine and it reverted to the crown in 1887. As American and Canadian transportation companies added shipping routes to Kootenay Lake, the mine became viable again.

Dr. W.A. Hendryx opened the Bluebell and started the first serious attempt at developing the huge body of ore. They began shipping down lake, then on to wagons crossing the border at Bonner’s Ferry and on to Sandpoint to meet the train. But even those funds ran out as the value of the metals dropped.

It wasn’t until 1906 that the mine once again became viable. The Canadian Metal Company under the management of S.S. Foweler, took it over and built a huge crusher mill to concentrate the ore.

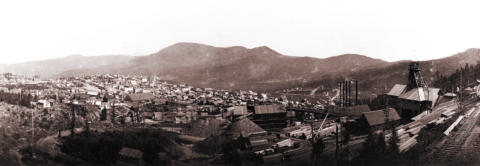

The workers arrived to a company town that they called Riondel, after the largest shareholder, a French aristocrat.

By 1914, there were over 200 men working in the mine and mill, and their families had all the benefits of a real Kootenay town. Church and school were in place as well as steamer wharves to reach the outside world.

Try as they may, the mine went all but dormant by 1928.

Bob Nichols writes in the October 13th, 1950 issue of the Vancouver Sun: Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company took over the old mines in 1948. By October, they were starting the first rock work.

A new crushing mill, both jaw and ball type, is being built just up from the lakeshore. New faces appear every day. Open spaces in the thick pine forest are filled overnight, it seems, by families determined to get in on the ground floor of mining jobs. Officials vary their estimates of the number of inhabitants will be needed. Some say 300 and others as many as 500. The town is growing all the time.

This will not be a mine of the old methods, but of modern technology, skilled miners and the know-how of the CMS Co. It will make a paying proposition out of the first lode mine in the interior of B.C.

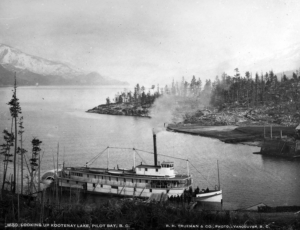

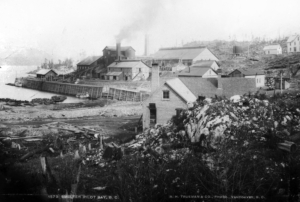

The Pilot Bay Concentrator and townsite of Riondel, circa 1897.

Photos courtesy of the Kootenay Lake Historical Society