Princeton’s Industrial Disaster 1910-1914

John George found an outcrop of limestone on the Allison property just three miles east of Princeton. He purchased the property then travelled to Vancouver and met with his Provincial MPP, Lytton Shatford and suggested an opportunity for a cement production plant.

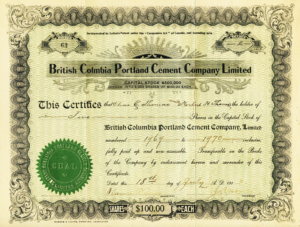

Shatford immediately rallied 13 of his business contacts with the idea. Without seeing the property or doing tests on the minerals present in Princeton, these gentlemen applied for, and received a charter for the Portland Cement Company, September 9, 1910, and began selling shares and bonds at $100 per share.

Mr. George was offered 1,850 shares for his 80-acre parcel, then was told he would receive the manager position when the factory was built. He was handed the responsibility of selling stock locally and with his efforts and the efforts of H.M. Budd, a Toronto stockbroker; they raised over $200,000 in capital.

At this point it became important to test the limestone and shale deposit for quality. Samples were sent to Rocky Mountain Cement Company in Blairmore, Alberta where it was reported that the grey material was satisfactory and the shale was excellent. It was found out later that the Great Northern Railway had secreted samples to a plant in St. Paul for testing as well, as they knew they would be the shippers of choice.

The spin went like this: ”The limestone and shale are of first quality and have been tested out in several laboratories and chemists found them entirely satisfactory for the manufacture of the highest grade of Portland cement. There is sufficient material on the property to keep the works running for hundreds of years with a capacity of 2,000 barrels (90,000 gal) per day.” This report sparked real interest with investors and by the end of 1912, $315,000 had been raised. All this without a single pound of cement produced.

The company was already sounding like a Ponzi scheme: “Bonds have been fully subscribed, which leaves them in the neighbourhood of $20,000 to place in order to supply sufficient funds to completely equip the plant. From the present estimate they have expended to date nearly $270,000 for all purposes, $30,000 of this amount will be returned to them by the adjoining Coal Company, for one-half interest in the railway spur when completed. They do not expect to sell more than $335,000 of the $400,000 worth of bonds which they are permitted to issue according to their bylaws. However, if conditions arise over which they have no control, they might possibly replace $350,000 of the present issue. With those $335,000 of bonds issued according to the present basis of sale, they would not issue more than 1,700 shares of stock. This number of shares given for the property would make a formal issue of not more than 3,600 shares of the 5,000 shares for which they are capitalized.”

These figures were to call attention to the fact that the profits accruing to the purchasers of the stocks and bonds, would realize handsome dividends. Of course, there were no profits accruing.

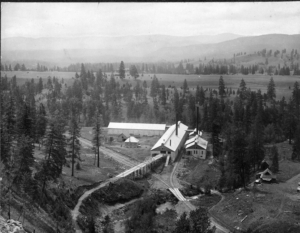

Estimates for construction of the plant were estimated at just over $400,000 for buildings and machinery. Before all this could take place, a couple of other items had to be dealt with. First, the Great Northern Railroad had to be convinced to bring a spur across the Similkameen River to the plant. This involved a large bridge, wye and 2 plant spurs. Estimates for bridge construction was between $60,000 and $70,000. The GNR agreed to a deposit of $30,000 with the rail company throwing in $5000 in good faith, the Cement Company had to raise the rest. This is where the second item comes in. There was a coal deposit on the property. Not great coal, but a large deposit. The adjacent property had an operating coal mine under the operational name of the United Empire Coal Company. Cement Company directors convinced them to invest in the rail spur to ship coal with the assurance that their coal would be used to create electricity in the cement factory. They threw $20,000 into the pot. The bridge and spur, along with a two-mile extension to the coal mine, was constructed in 1912.

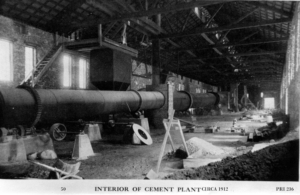

Construction had already begun using clay and stones from the property now that they could order by rail. The workers had installed a single rotary kiln and produced 250,000 bricks from local clay. The brick was used for boiler and drying settings. They received 5 rail cars of Clayburne kiln blocks. Lime could also be produced, but cement had to be imported. In 1912, they imported a full shipment of cement for $5.50 a barrel.

Workmen began to come in from all over the country to work on the project. The first group spent their time clearing trees and brush from the limestone deposit and removing the clay and shale layer. The deposit was only 500 feet from the plant so a tram conveyor was planned as well.

March 30, 1913:

“The employees of the Cement Works will reside on the new townsite of East Princeton which is only a ten-minute walk. Homes are being provided for them there by the townsite owners and they will be supplied with the conveniences of a modern city.”

Construction of clapboard homes did begin in 1912 with a promise of electricity, telephones and running water. The Methodist Church set out to build a church in the settlement and raised considerable funds. Rev. Osbourne officiated over the flock.

This is when the Budd Brothers came to Princeton. William James Budd, was an industrial builder from Calgary. He had been involved with the Calgary Power company and the Horseshoe Dam project that he failed to complete. His brother H. M. Budd was there to collect on stock subscriptions.

Budd was contracted for $10,000 to lay out the buildings and machinery to efficiently produce between 500 and 700 barrels of cement per day with a budget for 1912 of $200,000. He assured the company that he could build to produce 2,000 barrels day, then immediately left for Eastern Canada to tour Canada Cement Company plants to understand modern designs.

It has been reported in other journals that Budd was deeply involved in the planning of the Rocky Mountain Cement Company works in east Blairmore. Budd was also vice-president of the proposed Keystone Portland Cement Company plant in west Frank, which was never built. Construction of the Blairmore cement plant was delayed and its cement production was curtailed to deliberately depress share prices; the directors then sold the facility to the newly-founded Canada Cement Company at a bargain price and were rewarded with shares in that company. Similar tactics surrounding the consolidation of the cement industry across Canada and the creation of Canada Cement’s near-monopoly caused a national scandal in 1911 which was a factor in major shareholder Maxwell Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook) leaving Canada for England.

Within just few months the cost of the buildings, crushers, driers, kilns etc., had surpassed $235,000 with equipment arriving at a further cost of $125,000. Plans were in place to produce fine plaster from Gypsum mined at Coalmont (Welldo), all-purpose lime and a cement-based concrete. But still, not a pound is available in 1912.

Budd is given 60 days to start production in June of 1913. He gets an extension to Christmas and does start producing at that time as “Elk Brand” cement. He sells every barrel to Copper Mountain Mine and Allenby at under $2 a barrel. Cost of the factory exceeds $400,000.

The Directors are furious and seek advice on cutting expenses. They approach the Kettle Valley Railway which will skirt the property, for cheaper rates. As a result, Great Northern Railroad calls in their debt of $30,000 which still remains unpaid. They threaten to suspend service.

The United Empire Coal mine is sold to Princeton Coal and Land Company and they want to renegotiate the value of their coal to the plant. They want to drop a shaft to a better-quality lignite and feel that their only customer, Portland Cement, should assist in those costs. A geologist is called in to explore the coal vein on the cement plant property but it is found to be too high in ash to burn of required heat. Princeton Coal and Land start shipping their coal to Vancouver leaving the cement plant to buy the balance needed from other mines.

Then a geologist from the Department of Mines reports that “the limestone deposit at present being utilized, although pure, is not of great extent, and the present system of quarrying is rather expensive, but it is claimed that the company possesses other larger deposits of limestone farther up One Mile Creek.”

The blame shifts in the annual report of 1913 to Mr. Budd and his company. Reading between the lines of President J.A. Harvey’s report, it is clear that Mr. Budd had been a little dishonest with his ability to design and construct the plant to working order. Much of the $125,000 for equipment has gone into Mr. Budd’s company and the machines seemed to be well used and not operational. The foundations under the boilers fell apart and caused the boilers to sink. The kilns and mills are continually under repair through most of 1913.

The company called a special meeting in December 1913 to vote for refinancing. They voted unanimously to borrow $150,000 on current assets to restart the plant. There was considerable trepidation amongst the bondholders, as it was mentioned that they had not been able to collect on $45,000 in stock subscriptions locally. They didn’t want to borrow on assets already encumbered but not noted in the annual financial statements. Soon after, Treasurer C.R. Briggs resigned.

By July 8th, 1914, the plant was ready to begin production. The run was short as the machines once again broke down. In addition, the adjacent coal mine closed and the $30,000 note held by Portland Cement for the GNR bridge was reneged. Budd headed for Blairmore and never returned. Manager John George had already cleared out and soon after died in Saskatchewan.

James Budd sent his partner J.A. Osborne from Blairmore to take over as manager of the plant, but it was too little too late. The money ran out and the factory closed. The board tried to spin the closure as temporary and even tried to sell more stock and to collect on notes in the community, but to no avail.

War was declared soon after the closure and the men signed up to go overseas. The equipment was seized and removed, the rest salvaged and stolen. The bridge and spur remained until 1928 when the bridge was dismantled and removed to be reassembled over the Tulameen River at the Pleasant Valley Coal Company mine.

The ruins remain to this day and are part of a resort appropriately named “Princeton Castle” It is a destination for wedding photographers and family reunions.

Thank you, Robin Lowe. Princeton Museum

Ian McKenzie, Blairmore

Princeton researchers Evelyn McCallum and Lori Weissbach

BC Historic Newspapers